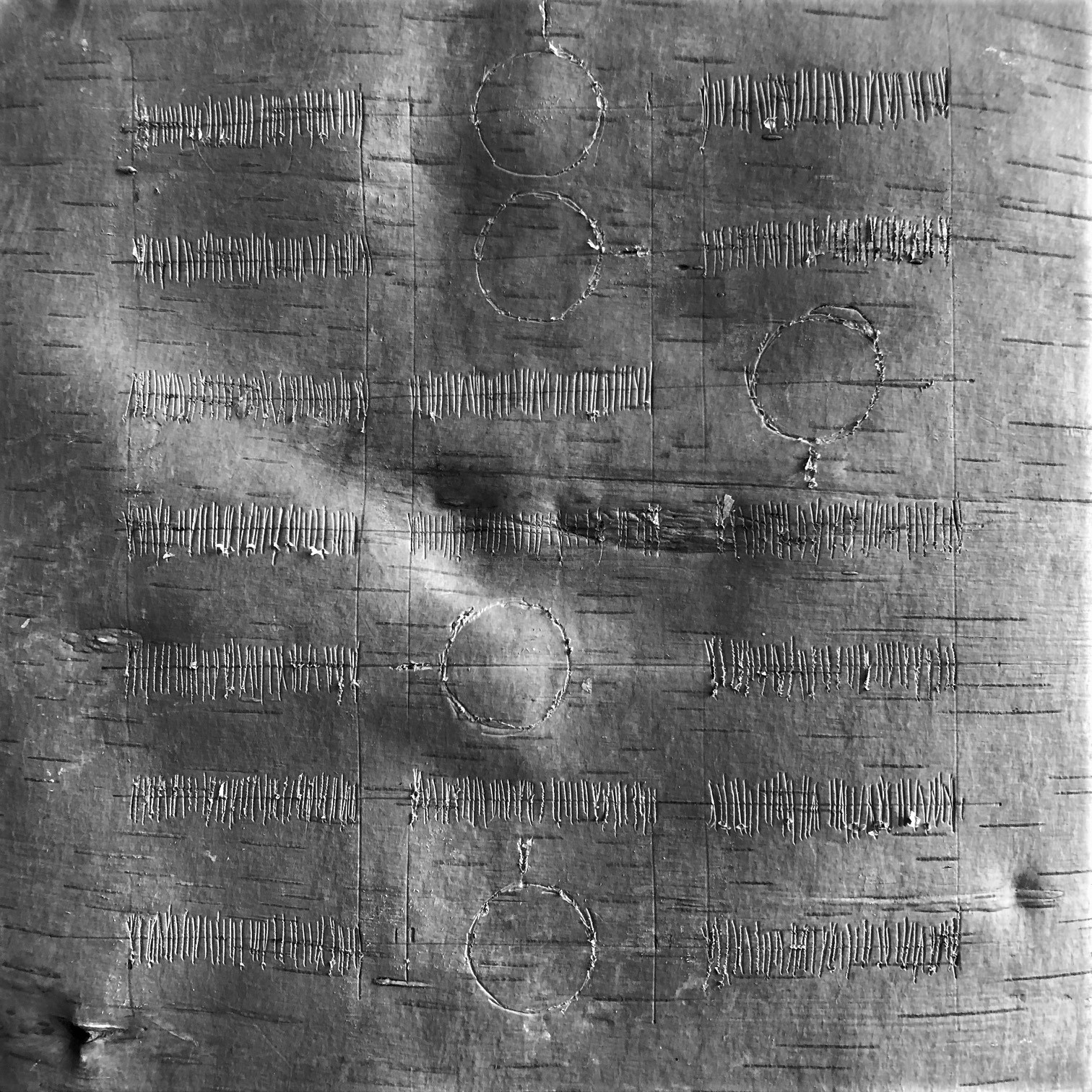

Carved birch bark graphical song notation: Onimikìg CG I, 2023.

TIMOTHY ARCHAMBAULT: This is the premiere of my new album, based upon thunder. I wanted this album to be about brontomancy, which is a practice of divining the future by studying thunder across, all the different tribes, but mostly within the Wabanaki Confederation, the Algonquins, Ojibwe, and so forth. A lot of my work has to do with divination, whether it’s the shaking tent ritual, 1 chants, or scapulimancy—which is the practice of reading scapulae or spealbones. The Naskapi practiced this, and even within my family, growing up, we would kill deer and be looking at their shoulder blades, for instance. We would also look at how the blade we used to do it got burnt in the fire—which is not scapulimancy, but it’s similar—to see if the animal was well-fed, if it was a good season for them. And, from that, you can make determinations, such as, “Oh, we have a whole herd over there. Should we go hunt them or not?” And it’s the same thing with thunder. What does it mean when you hear different types of thunder, and how do they relate to future weather, or in terms of prospective luck, or for the tribe and its future. I’m really interested in the question of what it means, spiritually, to call our ancestors. I’m using music as a conduit or instrument to receive them, to ask them for help, or just to give them some symbolic gestures of our lives here, what we’re going through, and then sending it out to the universe. The album has eight songs originally inscribed in birch bark in a traditional form of notation and mnemonics from up north, along the north of the Saint Lawrence River in Ottawa all the way down to Connecticut. My Memere (grandmother) was the first person who taught me how to carve birch bark when I was growing up there, in the town of Coventry. Each song highlights an extended flute technique that represents, symbolically, a different type of thunder. In between those, there’s also the warble—when air pressure causes a flute to attempt to play two notes at the same time—which I think of as a horizon, which the melody plays off of. My work brings in traditional elements, in keeping with the methodology of our heritage; whether that’s carving birch bark, inscribing it, or using other means and other materials. It’s about keeping that tradition alive, but in a completely new way; which you yourself have done, as well, with your notation. We have so many different materials we worked on, a lot more than people know. For me, it’s about evolving the flute—keeping a traditional framework, but with all new notation or types of sounds. When I meet young flute players, I tell them, “It’s not about copying me, or copying others. It’s about finding yourself, right?” The best teacher is the one that can bring out the student, and what they have that’s so unique to bring into this world. And at the same time, I might say, “Look back upon your tribe. What is inherent in the tribe? What are the songs?” If you don’t know, then you start to create it within yourself. Your physical habits and behavior, the way you are, is already continuing the tribal collective social consciousness. You have to hone in on it, and then make it unique. It takes time, and it’s not easy.

RAVEN CHACON: Do you teach? Do you have any students?

TA: I’ve done a couple seminars here and there. It’s difficult—because of time and my profession.

RC: In terms of the tradition of flute playing that you’re in, is there a younger generation studying it or are they from a different tradition?

TA: Usually they are from different tribes. Along with some other people up in Maniwaki in Quebec, we’re actually in the process right now of trying to hone in on birch bark carving in relation to song, flute playing, and drumming—efforts toward keeping all that alive, in addition to the language as well. Other people are doing this already on the res, and I want to try to help them, give them in information, and then they can use it according to what best suits the tribe’s needs, especially for the kids.

RC: And we’re talking about Algonquin nations?

TA: Right now, I just deal with Maniwaki, Metis Nation of Quebec, and the Kichesipirini Algonquin Nation up in Pembroke, which is not even recognized by the Canadian government. I focus on the largest one, which is Maniwaki, since I have friends there and elders that I know. We’re try to help sustain the language, the music, the hunting techniques—everything from getting licenses for killing moose for food all the way down to the old techniques of birch bark carving. And that practice is not just about music notation or mnemonics—birch bark was also used for crafting different types of bowls, bags, and utilized in other functional tasks such as curing and storing meats.

RC: We were talking about the warble as a technique—can you say more about that?

TA: On the technical side, the warble is a multiphonic oscillation. It’s basically a note that is sounded, and reverberates between the low tonic note and the high tonic note, meaning the octave. A typical vibrato vibrates between one note and the second note closest to it. In the Western methodology, the warble is going up to its octave, eight different chromatic tones higher, and back down, in rapid succession, which is quite fascinating. Some instruments, like clarinets, can do it. I think bassoons or other different woodwinds can do it in the classical genre. For me, it’s a spatial thing and I’ve always been attracted to it. A lot of tribes, like some of the Ojibwe and the Algonquins, used to soak their flutes in water. They thought it made the sound better, because they were mimicking the vocalization of throat rattling, and they called it the horizon, which the melody would float off of. I’m drawn to it—I love the mechanized sound of it. I love the machine aspects of an acoustic instrument. It’s a usually a piece of cedar or alderwood, depending upon what’s regionally specific to each tribe. Each had its own culture, musical history, and geographical resources that contribute to the making of the instrument. I’m still shocked to this day at some of the tones that can come out of it, especially when you think about how it’s just a piece of wood. I think if someone heard it and didn’t know that, they might think it was a machine. It’s about the rapid succession of breath, and pressure, and a threshold in the instrument that together starts off this rapid fluctuation of sound. You can’t change the speed so much once it starts—it stays pretty constant. And then, it’ll shut off. This is not something I invented at all; it was always there. You can hear it going back to old wax cylinder recordings from the early twentieth century or even the late nineteenth century. Not all tribes used this, but a lot did, from the Plains all the way up to the Ojibwe. The sound can mimic different types of bird calls. It could be used at a lake and the sound would ricochet off the water and carry over tonally as a signal for different types of war parties. It’s a crucial component of the flute that I know. I want to see how far I can go with structuring music around that, as the ancestors did, while also bringing in new techniques.

RC: Can you explain more about this horizon of melody—are you talking about actually reading the landscape to inspire a melody?

TA: Sometimes. For me, the warble’s the ground, or the horizon—that’s the edge. The warble has to be on the instrument’s lowest note; it can’t be created on any other note. I can make multiphonics on other holes of the instrument, but it’s always the lowest note that is the warble. That sound is the ground, in some sense. Symbolically, it’s the foundation that everything else floats above. If I were looking at the earth, or a silhouette of a mountain range, for instance, the warble will be the stone or the rock, and the light would be the melodies.

RC: That’s really beautiful. I’ve been using a similar idea in a lot of my pieces, where there’s a fundamental note and then the partial ones are like stars. I actually draw them like that, as little harmonic diamonds above a line.

TA: With a mountain, you can think of it in terms of time versus pitch: A mountain peaks at different intervals, which could be compared to the rate of the warble, or like how a higher frequency or a higher pitch eventually goes down. Your base melodies could be based upon the ground, and the other ones float off of it, not unlike these natural forms.

RC: Is there an Algonquin tradition of actually using the contour of a range or a landscape as compositional material?

TA: It’s less visual, and more audible. It’s like the myth of the waterfall; it’s mimicking waterfalls. There are songs solely related to the water, as you know, and then there are waterfall songs, right? The flute had to mimic waterfall sounds—“Song of the Laughing Waters,” for instance, is a big one. But there’re other ones for mimicking birds, war calls, even ones meant to be taunting, ridicule songs between two different war parties. I’m interested in this question of how do we mimic nature or have nature inform us of our compositions in a less visual way?

RC: I’m speaking right now from Sámi land, and that’s definitely a part of the joik tradition: Taking the contour of the line—and I know that this is something that’s done by Lakota singers as well—of reading the actual contour of a landscape. It becomes very site-specific, composed from the location where one is standing. If one were able to go back and maybe analyze a melody, they would say, “Oh, there’s a peak here and there’s a dip here.” That’s where the song was composed from, this valley, for instance.

TA: We have the perceptual, which is what I was talking about, and in Lakota, it’s also the analytical. In indigenous culture—specifically in Native American, or American Indian, indigenous culture—the spatial relationship between the body and the Earth and the universe is very spherical. In the circle and the cross—you’re a point. It’s very analytical. In terms of the perceptual—we’re standing and we’re looking out at the horizon; we can create the composition from the earth there. The other perspective is the analytical—you’re looking from above, scanning around the horizon of your locale, and basing your composition on that. It’s a radial composition. What you see in a lot of modern composers is a point, and then that’s the time. It’s something one can think about—the analytical versus the perceptual in relation to compositions, and how we can read them off the landscape. What’s it like in the Navajo, Raven?

RC: I’m sure there is something like that, but I don’t know if there is a tradition of songs specifically being readings of the landscape. I think it would probably be more related to seasons or situations, rather than a fixed geographical reading.

TA: I go up to Canada when I can as part of trying to learn more about my culture, and the older I get it seems that it becomes less symbolic or metaphorical and instead very pragmatic. It has become about very practical things that they did to survive. Over the generations, things became lost in translation, or in the evolution of the tribes it’s been watered down. And if you go back, meanings were very precise and functional. And what I’m trying to get to here is related to what you said, about being more abstract. It’s not something that we can point to, physically. I think it’s way more ethereal than that. But it’s through a conscious understanding, a realization of our world, our surroundings over time, that you start to look at things in a very fine-tuned way. This helps inform the music.

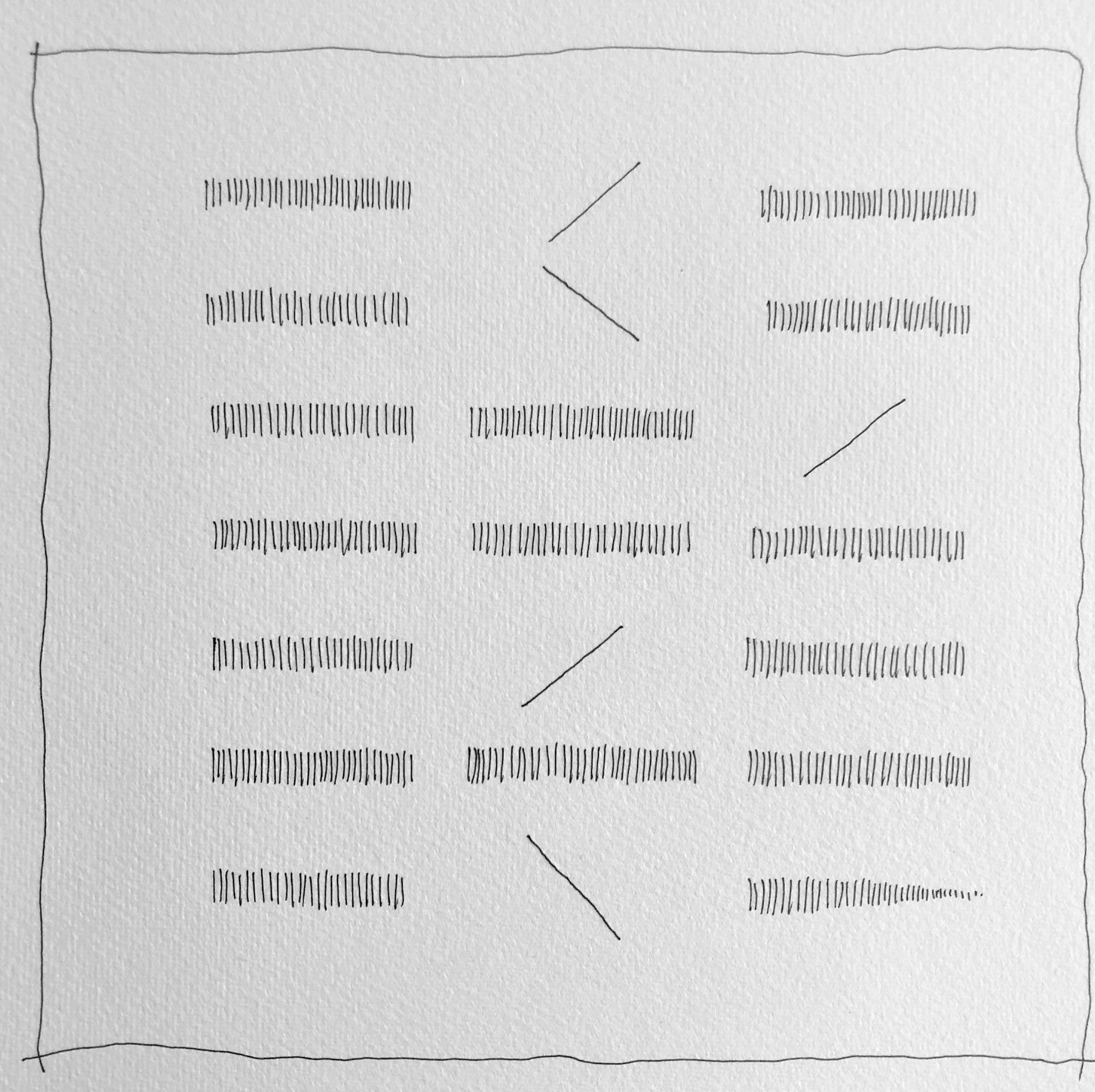

Graphical song notation: Onimikìg CG I, 2023.

RC: You’re also an architect and you’ve worked on some massive projects, which was something that was I blown away by when I first met you. You have this other practice and you balance that with your music as well as the ongoing work of keeping a musical tradition that you’re a part of alive. Does architectural work influence your compositions, improvisations, or the drawing of notations, even your own analysis of what you do and the tradition you’re in?

TA: The structure was a bigger element of the composition when I was younger, when you first met me. How music and architecture can both be all planned out. Everything had to have a certain type of climactic point. Now, I would say it’s more spatial. With architecture now, I could care less about the materials. That’s superficial for me. I love the structure because of what it’s doing, rather than what it looks like. I do care about the spatial sequencing, how a building frames space. My music is more spatial now, too.

RC: This might be about actual movement through a space, or the position in which you’re aiming your instrument. Even volume, of course, gets activated because of space.

TA: When we do our performances, we are building our circle, and it depends upon the spatial locale we’re going to. That’s the context in which we’re going to play the piece, and it depends upon what we’re thinking about, what circulation already exists within the space, and then how we can counter it—that informs the composition. It’s also more than that, even the idea of space—I am still mystified by it. It’s something within our whole body. We’re breathing this stuff in and we’re breathing it out. It’s in our bodies. If you look at the atomic spectrums, there’s a complete density of thresholds. When you get into the atomic world of relativity, it’s all dense—we’re all related, all materials, molecules, and so forth. That’s why I think the spatial frame, what’s being contained, the space itself, is far more important than the actual physical container. Musically, I would say I’m concerned with the same thing: The ethereal nature of sound within the structure of composition. The nature of sound itself is very similar to space for me. Space is a medium which music can ricochet off of. It reverberates off the molecules in space. It’s unbelievable, if you think about it. It’s a beautiful thing. The dematerialization of sound is just incredible. And the dematerialization of space in architecture is similarly incredible.

RC: I always hesitate to consider anybody in the presence of music to be just an audience, but, of course, architecture considers bodies and people. And if you’re thinking about spatialization, you’re thinking about your own ears, and your own reaction as the performer in a feedback loop. Then there’s the feedback loop that can happen with the audience as well—you’ll be playing in a space, which, as we’ve been discussing, has properties that are going to influence the music, so are there considerations of how the people in the space will also be a part of that?

TA: Well, in architecture, we have post-occupancy evaluations. We actually go back to projects we worked on six months to a year later, and evaluate how the actual space we made works with the people in it. With music, I haven’t dealt with that enough. It’s not something I’ve focused on yet. Maybe I will when the time is right. I think it’s intriguing, because why should it be composers or the architect just sending out? Why shouldn’t the occupants, or, as you said, the audience, participate in the composition? Then it would be a result of both. I don’t think it has been done enough.

RC: Even that term that you’re using, “occupants,” is really interesting. It’s a nice way to think about gathering inside of a space, whether it be a concert hall, or anywhere where music is. And not necessarily a place where music is being hosted; music is the host, and we’re all there to be in the presence of it.

TA: It’s interesting to think about this in relation to the Ghost Dance, which is really beautiful as a form of cultural retrieval and revival. When the government was oppressing the tribes, they allied themselves together to try to save their cultures and traditions. They would bathe, do the songs—songs that were multimetric—and dance for hours. Someone would come up with either a crow feather, or a white cloth, and flash it in front of their face before they passed out. After that, no one touched them. And then they would dream. Maybe they would have a dream about a meaningful thing in life, or maybe it was about a song. Regardless, they would bring it up in the next meeting or circle discussion. And they’d say, “I had a dream in the last dance about this song.” Then they would sing it—they would learn that song. And then they would go back, and sing it, and do it again. It was about going deep into their minds, getting out what’s in the subconscious, bringing it out, and then collectively participating. Collectivity is in our culture, we just have to refine it. How do we do that in a way that’s beneficial, today, in the modern world, outside of that tradition?

RC: I had an experience like that, not quite like the Ghost Dance, but we remember during the pandemic, there were streaming concerts. And there would sometimes be a real-time chat function, which is something you don’t normally have during a show. I can’t talk to you during a concert and say, “Hey, Tim, this is great. Wow.” But, as I was playing one of these concerts, I could read in real time the conversations people were having about what they were hearing. Generally, if people were talking during your concert, you would be very annoyed. I was finding myself reading the comments though, as I was playing, because I could see them. And this was its own feedback loop of interaction. Even with a slight delay, it became part of the improvisation for me. Obviously, it was affecting me—it was another thing I was playing to. As we’re talking about developing, or at least being aware of these interactions, I think that’s something that I could see as a potential scenario for this kind of interaction. But I want to back up to before this new album too, and ask you about Chìsake (Ideologic Organ, 2021)—what those songs are, how that got released, the collaboration with Stephen O’Malley and his label.

TA: That was just by chance, purely by chance. I had released the album beforehand. It was based upon shaking tent songs, which are about ancestral divination. A person would get into the tent, they would shake wildly—it was like the person got possessed. Then they would have visions of the future, usually embodying their totems, their spirit animals. And then, you tell it back to the tribe and figure out how the future’s going to be based on this encounter. Or it could be black magic type stuff, where someone’s pissed about you, and your family’s going to die in the next three years, and so forth. It goes back and forth and can be a mixed bag. Ancestral divination really resonates with me, because when I play my music I think about my ancestry all the time.

RC: I got one of those early pressings on CD.

TA: Stephen and I mastered it, but I originally released it on my own label. The second release came about because I just emailed Stephen during COVID. I was in between some projects and I’m not sure what inspired me to get in touch, but I did, and said, “We should do some collaboration.” And he was like, “Yeah.” That was it. He said, “Look, send me over some of your music.” I sent him The Ghost Dance (self-released, 2017), Chìsake, and some other stuff. He liked Chìsake the best and wanted to make a vinyl of the album. I said, “Let’s do it. Sure.”

RC: Amazing album.

TA: We remastered it slightly from the CD because he was working at the time with this Austrian guy and they just wanted to tighten up some of the mastering for vinyl. We’ve been continuing our conversation ever since. He said it’s about bartering. When you’re working together, things come and go with friends—you join up, you go away, you come back, and so on. It depends upon where we are in life. And I just love his work, too. The Sunn O)))) record The Grimmrobe Demos (Hydra Head Noise Industries, 2000) is one of my favorite albums. I like his solo stuff, too. I have a lot of his music that’s just him playing for an hour. The simplicity and how the modulations occur with his feedback—I like it very much.

RC: I wanted to ask you about recent work you’ve been doing in art venues, including a trumpet piece and your collaboration with your partner CYJO.

TA: We each have our own work but we get together when needed. We have done a lot of work together, under the moniker thecreativedestruction, that is about the indigenous schools. We’ve done a lot of drawings on that—which we have prints of, too—about the schools set up for the assimilation of indigenous people. The project you’re referring to with the trumpets is Infinite Honor, 2017. We dedicated it to all veterans, indigenous veterans, and so forth. And that’s because my father committed suicide. He was a veteran—served in the U.S. Army Connecticut National Guard during the Vietnam era. At the time we came up with the piece twenty-two veterans killed themselves every day. The rate has gone down a little bit, thank God, to seventeen. For the performance of the piece we would play seventeen times across different spaces of the Pérez Art Museum in Miami during their operating hours. It could seem random, that we just started playing “Taps,” but it was done on Veterans Day to bring this up for people to recognize and think about what’s going on. I studied trumpet—grew up playing classical trumpet and now I play in Bugles Across America, which basically means I play at veteran funerals. In the late nineties, Congress passed a bill stating that they would limit the number of bugle players for such events because they didn’t have enough funds. My uncle was an officer in the Navy and when I went to his funeral a tape of “Taps” was played on a boom box. It was the most disturbing thing I had seen in a long time. I promised myself I would never allow that to happen if any of my other family members who were veterans or in the military had a funeral. At least, not while I’m around. I would play the bugle for them, and I did this for my grandfather, my uncles, and my father. Another recent project I’ve done with CYJO is called The Offering, an iteration of which will be installed April 8–16 at a space in Greenpoint called 44LLC. It’s a series of tobacco piles, very small, based on the tradition of how when you take anything from the Earth, you have to give something back, right? Whether it’s killing an animal, or taking a flower, having a death in the family, you give a little prayer back. We have ceremonies for that, where tobacco’s given back. The space where the piece is installed determines how many piles of tobacco are laid on the floor. It’s dedicated to each indigenous woman that’s still missing or has been murdered amidst a severe and ongoing crisis. It’s astounding how many women disappear each year. It goes all the way back to the colonial era when tribal women would be raped as part of an outside attempt to annihilate the culture. This happens in Canada, the United States, and every single small town where the highways are going through. It’s a huge infrastructural problem. There are different systematic levels to it—it comes from the outside, from corruption, the federal government, drug cartels, and even internally from within the tribes. It happens to thousands of women each year and the annual number goes up and up. It astounds me how nobody does anything, and the infrastructure’s not set up to find out why. But then, you realize, nobody wants you to find out why. Our piece is about calling attention to that. And, thankfully, Laura Ortman will be playing her wonderful music and dedicating the piece at the opening of the show on Saturday, April at 4pm.