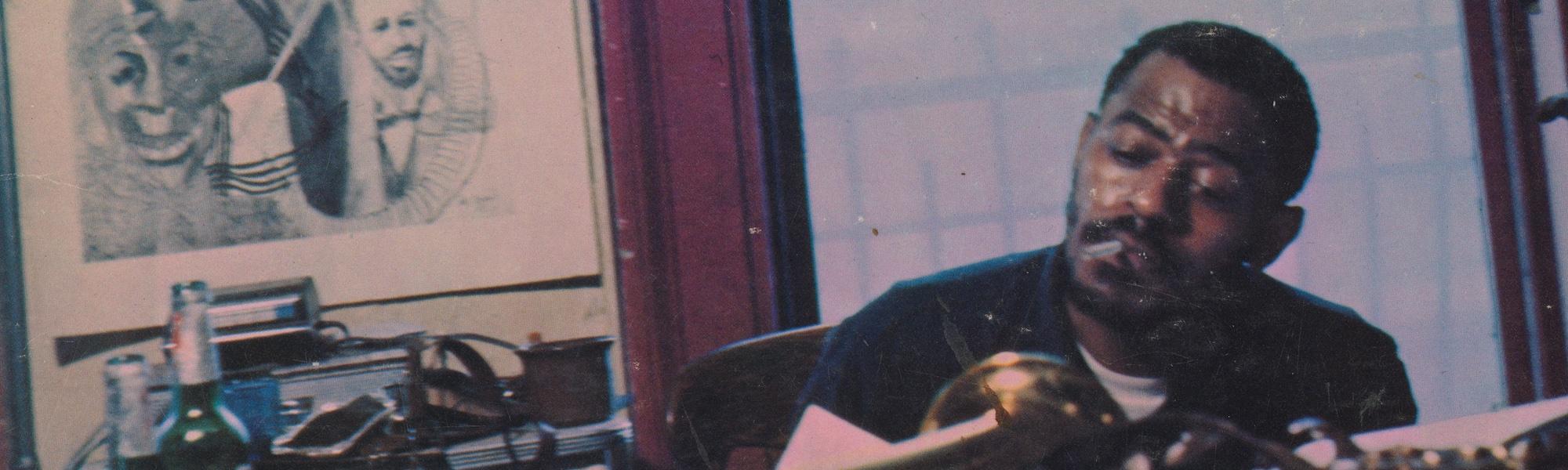

Front cover of Archie Shepp’s Attica Blues (detail), 1972.

Translator’s Introduction by Gabriel Bristow

Few critics took seriously the politics of free jazz (or, as its first wave of musicians dubbed it, the “new thing”). Fewer still chronicled what the musicians had to say about it. Val Wilmer was one of the exceptions, approaching the music and its politics through words and photographs, dealing with the whole as seriously as the musicians dealt with their music. It is thanks to her pioneering work—often in trying circumstances—that we can glimpse the social and intellectual life that underpinned the recorded music that is only the tip of the iceberg, however beautiful a tip it may be.

“The Meaning of Attica” is a title that expresses its purpose with the same elegant directness that characterizes the album it’s about. With minimal adornment, Wilmer lets the words of the musicians do the work—not of interpretation, but of explanation. This is the background to the music—a window onto the political and emotional content of its form and the economics of its distribution and reception—rather than a post facto theorization. The meaning of Attica is found in the music itself.

While the music itself was sparked by the Attica uprising of September 1971, it was also the product of the wider political and aesthetic pressures of the conjuncture. The flames of the “fire music” (to borrow the title of an early Shepp album) of the ’60s had not been fanned the way the musicians had hoped for. Despite the promise of a great coming-together of black music prophesied by Amiri Baraka in his 1966 essay “The Changing Same” and fleetingly realized when James Brown urged saxophonist Robert “Chopper” McCullough to “blow me some ’Trane, brother” on his 1970 single “Super Bad,” by the time Attica Blues was recorded in 1972 the difficulty of holding the “new thing” and R&B in creative tension was becoming ever more apparent, echoing the increasing discord of the political movements with which the music resonated. This left the “avant-garde” in a tight spot. And it’s out of this pressure-cooker of aesthetics, politics, and economics that Archie Shepp and his collaborators managed to distill Attica Blues. The presence and orientation of the masses of black people in the US could no longer be second-guessed—the musicians knew they had to meet the people where they were. While this was far from the first “avant-garde” album to attempt to do so, it was perhaps the most impressive in scope. Finely arranged and produced, Attica Blues is both intricate and monumental in its construction, piecing together a panoply of black expressive forms to politicize the memory of the Attica uprising. It is at once populist and pedagogical. This is borne out in Beaver Harris’s words to Wilmer below, and comes across all the more strongly when returning to the album in the light of this interview, as the music ferries the listener from dance to contemplation and back, breaking barriers between modes of reception. Meeting the masses where they are, Attica Blues simultaneously aims to raise them up (“Whenever I think of steam / When I’m flying high / Like an eagle in the sky”). 1 Or to put it in the stark words of Amiri Baraka, Attica Blues links up “what is direct with what is advanced.” 2 It is a portrait of a people in movement, in flux even, fighting for their lives and remembering, through music, that “even the dead will not be safe from the enemy if he is victorious.” 3

“Le Sens d'Attica,” reprinted in Jazz Magazine 538, 2003.

“The Meaning of Attica” by Val Wilmer

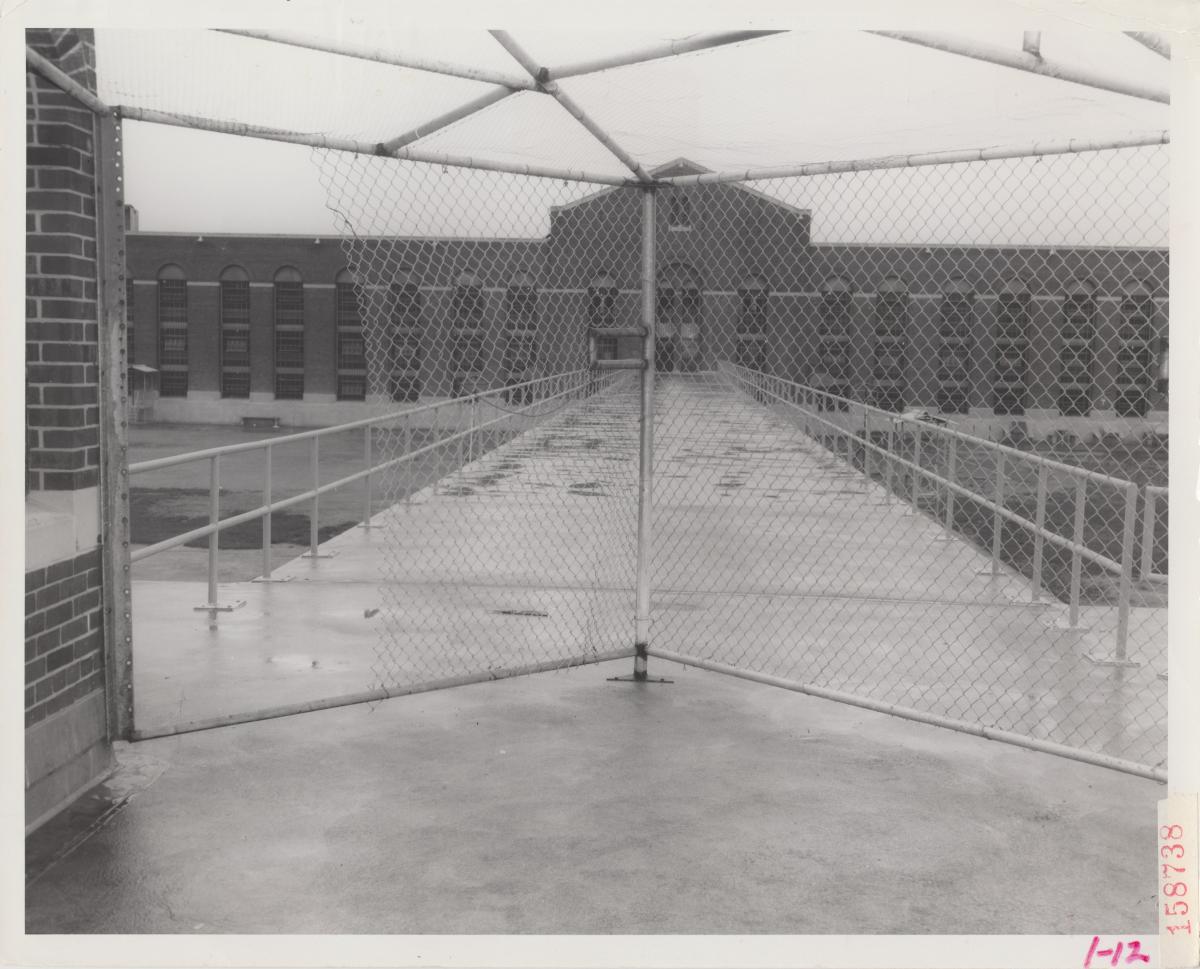

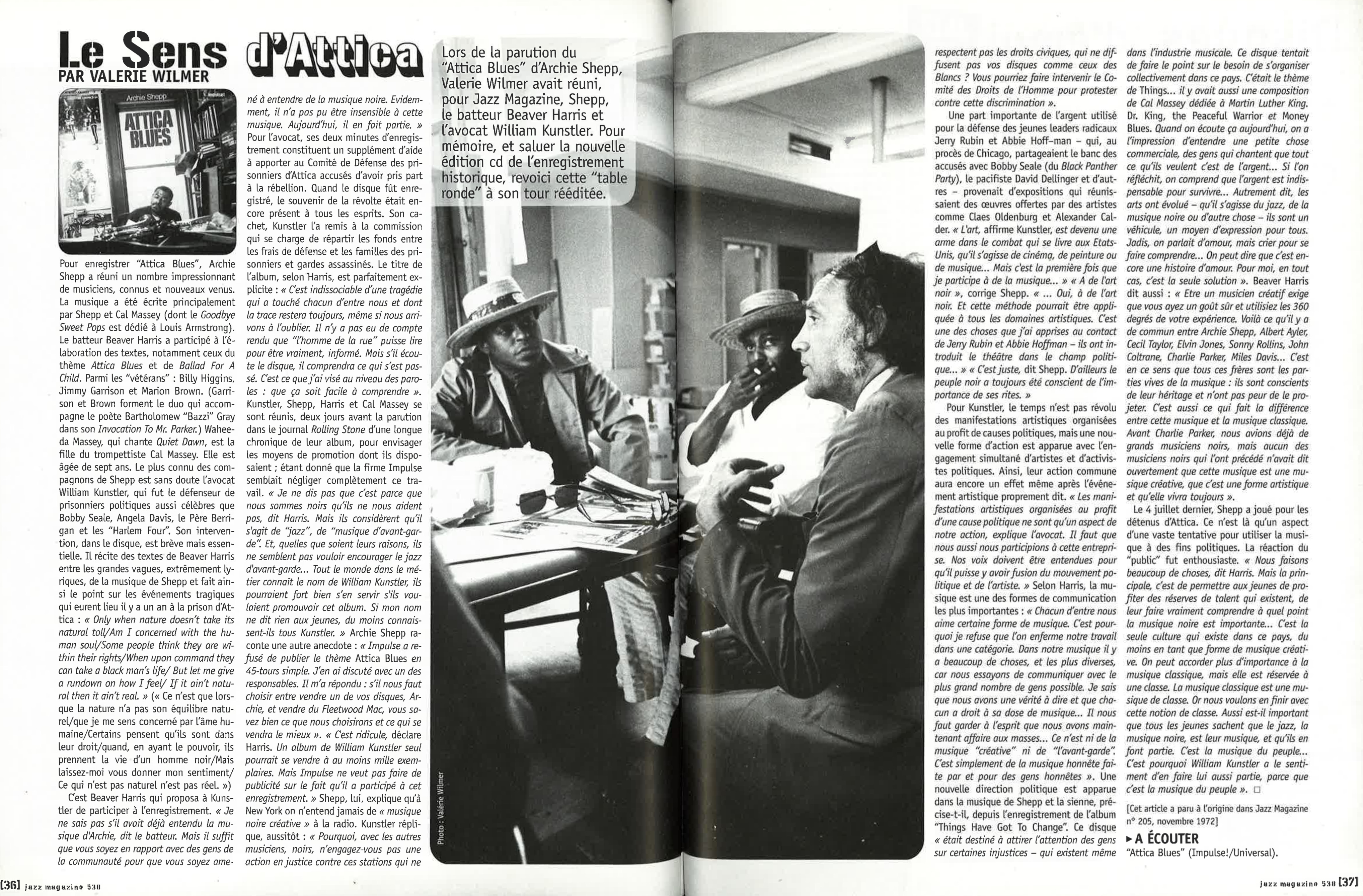

To record Attica Blues, Archie Shepp gathered an impressive number of musicians, well-known and newcomer alike. The music was primarily written by Shepp and Cal Massey (including “Good Bye Sweet Pops,” a composition dedicated to Louis Armstrong). The drummer Beaver Harris was involved in writing the lyrics, notably those of the title track “Attica Blues” and “Ballad for a Child.” The session’s “veterans” include Billy Higgins, Jimmy Garrison and Marion Brown. (Garrison and Brown form the duo that accompanies the poet Bartholomew “Bazzi” Gray on his “Invocation to Mr. Parker.”) Waheeda Massey, who sings “Quiet Dawn,” is the daughter of trumpeter Cal Massey. She is seven years old. The best known of Shepp’s comrades is undoubtedly the lawyer William Kunstler, who has defended political prisoners as famous as Bobby Seale, Angela Davis, Father Berrigan and the “Harlem Four.” His intervention on the record is brief but essential. He recites Beaver Harris’s words between the sweeping and extremely lyrical waves of Shepp’s music, taking stock of the tragic events that took place a year ago at Attica prison: “Only when nature doesn’t take its natural toll / Am I worried with the human soul / Some people think they are in their rights / When on command they can take a black man’s life / Now, let me give a run down on how I feel / If it ain’t natural, then it ain’t real.”

It was Beaver Harris who invited Kunstler to participate in the recording. “I don’t know if he had already heard Archie’s music,” said the drummer. “But just by being involved with people from the community you’re bound to end up hearing black music. Obviously, he couldn’t have been indifferent to this music. Now he’s part of it.” For the lawyer, his two minutes of recording constitute supplementary support for the defense committee of the Attica prisoners accused of taking part in the rebellion. When the album was recorded, the memory of the revolt was still present in everyone’s mind. Kunstler donated his fee to the committee in charge of distributing funds for defense costs and for the families of the prisoners and guards assassinated during the uprising. According to Harris, the album’s title is perfectly explicit: “It’s indissociable from a tragedy that has touched all of us and will remain with us forever, even if we manage to forget it. There hasn’t been an account that the ‘man on the street’ can read to be truly informed. But if he listens to the album, he’ll understand what happened. That’s what I aimed for with the lyrics: something easy to understand.” Two days before the publication of an in-depth article covering the album in Rolling Stone, Kunstler, Shepp, Harris and Cal Massey got together to discuss the promotional means at their disposal given Impulse’s seemly total neglect of the task. “I’m not saying that it’s because we’re black that they don’t help us,” said Harris. “But they think it’s about ‘jazz,’ about ‘avant-garde music.’ And whatever their reasons, they don’t seem to want to encourage avant-garde jazz. . . . Everyone in the business knows William Kunstler’s name, they could easily make use of it if they wanted to promote this album. If my name means nothing to young people, at least they all know Kunstler.” Archie Shepp had another anecdote: “Impulse refused to put out ‘Attica Blues’ as a 45 rpm single. I discussed it with one of the people in charge. He told me straight: if we have to choose between selling one of your records, Archie, and selling Fleetwood Mac, you well know what we’re going to choose and what will sell best.” “It’s ridiculous,” declared Harris. “An album by William Kunstler alone could sell at least a thousand copies. But Impulse doesn’t want to publicize the fact that they participated in this recording.” Shepp explained that in New York one never hears “black creative music” on the radio. Kunstler replied immediately: “Why don’t you—with other black musicians—file a case against these stations that don’t respect civil rights, that don’t play your records like they play white people’s? You could bring in the Human Rights Committee to protest against this discrimination.”

A significant part of the money used for the defense of the young radical leaders Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman—both of whom sat on the accused bench alongside Bobby Seale (of the Black Panther Party), pacifist David Dellinger, and others during the trial in Chicago 4 —came from exhibitions bringing together works donated by artists such as Claes Oldenburg and Alexander Calder. “Art,” affirmed Kunstler, “has become a weapon in the struggle that’s underway in the US, whether it’s cinema, painting, or music. . . . But this is the first time I’ve participated in music—”“In black art,” corrected Shepp. “. . . Yes, in black art. And this method could be applied to all artistic domains. It’s one of the things I learned from Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman—they introduced theater into the political arena . . .” “That’s right,” said Shepp. “And incidentally, black people have always been conscious of the importance of rituals.”

For Kunstler, the era of organizing artistic fundraisers for political causes is over, superseded by a new form of action involving the simultaneous engagement of artists and political activists. As such, their common action continues to have an effect after the artistic event proper has ended. “Artistic fundraisers organized for political causes are only one aspect of our struggle,” explained the lawyer. “We too need to participate in this enterprise. Our voices must be heard in order for there to be a fusion between the political movement and the artist.” According to Harris, music is one of the most important forms of communication. “Each one of us likes certain kinds of music. That’s why I refuse the idea that our work could be confined to a single category. There’s a lot of things in our music, many diverse elements, because we try to communicate with the largest possible number of people. I know that we have a truth to tell and that everyone has the right to their dose of music. . . . We have to keep in mind that we’re now talking about the masses . . . this is neither ‘creative’ music nor ‘avant-garde.’ It’s simply honest music made by and for honest people.” Harris explained that a new political direction had appeared in his and Shepp’s music since the recording of the album Things Have Got to Change (Impulse!/ACB Records, 1971). The latter “was intended to draw people’s attention to certain injustices, even ones that exist in the music industry. The record tried to account for the need to organize collectively in this country. That was the theme of Things . . . it also had one of Cal Massey’s compositions dedicated to Martin Luther King. ‘Dr. King, the Peaceful Warrior’ and ‘Money Blues.’ When one listens to it today, one has the impression of listening to something a little commercial—people singing that all they want is money . . . [but] if we think about it, we understand that money is necessary for survival. . . . In other words, the arts have evolved—whether jazz, black music, or something else—they are a vehicle, a means of expression for everyone. Before, people used to speak about love . . . but screaming to make yourself understood—we could say that’s still a love story. For me, in any case, it’s the only solution.” Beaver Harris had this to add: “To be a creative musician, you need to have a strong sense of taste, and to use all 360 degrees of your experience. That’s what there is in common between Archie Shepp, Albert Ayler, Cecil Taylor, Elvin Jones, Sonny Rollins, John Coltrane, Charlie Parker, Miles Davis . . . it’s in this sense that all these brothers are the living parts of the music: they’re conscious of their heritage and aren’t afraid to project it. That’s also what makes the difference between this music and classical music. Before Charlie Parker, we already had great black musicians, but none of the black musicians that came before him said explicitly that this music is a creative music, that it’s an art form and that it will live forever.”

On the last Fourth of July, Shepp played for the inmates at Attica. This was just one aspect of a vast effort to use music for political ends. The reaction of the “public” was enthusiastic. “We do lots of different things,” said Harris, “but principally it’s about allowing young people to benefit from the wealth of talent that exists, to make them truly understand just how important black music really is. . . . It’s the only culture that exists in this country, at least as a form of creative music. One could accord more importance to classical music, but it’s confined to a certain class. Classical music is a class music. But we want to do away with this idea of class. That’s why it’s important that all the young people know that jazz—black music—is their music, and that they’re part of it. It’s the music of the people. . . . That’s why William Kunstler feels part of it too, because it’s the music of the people.”