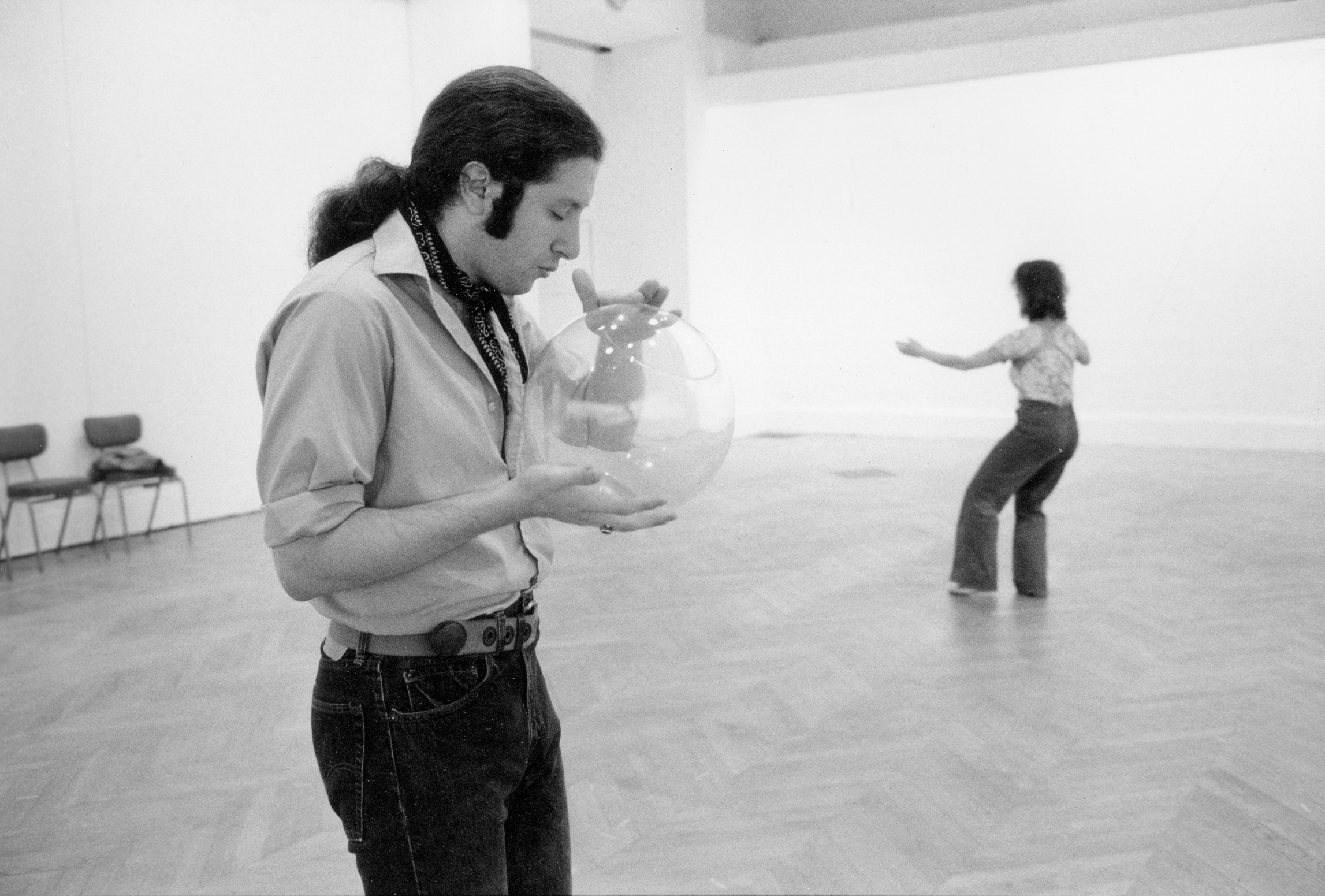

Charlemagne Palestine in performance, ca 1970s.

Consider the God Bear. In 1987, Charlemagne Palestine was invited to participate in Documenta 8, the massive, multi-site exhibition in Kassel, Germany, that by the ’70s came to serve as a de facto global survey of contemporary art. He had come to the program through curator Elisabeth Jappe, the founder of the Cologne alternative space Moltkerei Werkstatte, as part of a fifty-artist performance sidebar that mixed fellow countrymen ritualists Allan Kaprow and Terry Fox with German performance artists Ulrike Rosenbach and Die Tödliche Doris.

At the time, Palestine was in the midst of a relatively nomadic decade—the period he often caustically refers to as his “exile”—in which his signature musical performances, comprised of extended harmonically-rich lower-register piano playing, spirited singing, and audience confrontation, were few and far between.

Opting to tip-toe the parameters of his assignment, Palestine erected an enormous triple-headed and double-bodied teddy bear sculpture and requested that it be on display throughout the one-hundred day festival. Made from real mohair and standing nearly twenty feet high, the piece cost about 100,000 marks (a cool $160,000 in today’s US dollar) and needed to be transported by two trucks, assembled by a crew, and later positioned by crane. It eventually served as the centerpiece of a performance at Documenta called Auf der Suche nach God-Bear (In Search of God-Bear), in which the artist placed smaller bears at the effigy’s feet in reverence. During the ceremony, he sacralized the work’s spiritual influences: Andy Warhol, who had died that February following a gallbladder surgery and Joseph Beuys, who passed away the previous year, as well as Richard Steiff, the German designer of the earliest mass-produced teddy bear.

God Bear crowned a life-long connection with stuffed animals. Palestine recalls that he had always been drawn to them, arranging his childhood collection in circles and confiding in it, a habit that extended even into his early teen years. “My first acquaintance, , , , with “”otherr beingzzz”” fromm another somewhereezz, , (animism) like most western childrenn was through stuffed animalszz, , sooo, , they became my soul mates, , , my bestt friendszz, ,” he reminisced. 1

In the ’70s, during the heyday of his storied loft performances, Palestine took to placing plush toys throughout the space and atop his Bösendorfer piano, though by his own admission he took a sparse approach in step with the minimalist aesthetics then in vogue. In the mid-’80s, his obsession reached new heights when the Swiss curator Adelina von Fürstenberg arranged a trip for him to meet the design staff at the Steiff factory in Giengen, just outside of Stuttgart. There, he learned that although the company had perfected plush toy manufacturing, the true origins of the teddy bear could be pinpointed to a Russian-Jewish candy store owner in Bedford-Stuyvesant, whose shop was a straight shot down Nostrand from Palestine’s childhome home on Emmons Avenue in southern Brooklyn. He took particular shine to the company’s lead designer Jörg Junginger (great-grandnephew of its founder, Margarete Steiff) whom he subsequently conscripted to co-design the God Bear.

Perhaps there was something in the air, as God-Bear emerged at a moment when several notable artists were toying with anthropomorphic childhood artifacts. More triumphant than maudlin, Palestine’s devotional teddy contained no trace of the anguish or psychoanalytic family drama sometimes attributed to those of his peer Mike Kelley, whose use of stuffed animals was beginning to take shape not long before with works such as More Love Hours Than Can Ever Be Repaid, 1987. Nor was there the double-edged smirking of subsequent mammalian sculptures—Jeff Koons’s West Highland Terrier topiary Puppy, 1992, or Paul McCarthy’s proto-furry Skunks, 1993, and Spaghetti Man, 1993—although there was a strand of in-your-face American garishness far from the comparatively clinical atmosphere of Annette Messager’s Mes Petites Effigies, 1989–90, a series of plush-doll tapestries. In part because his bear spilled into the public square, Palestine’s angle was messy and exuberant, a sort of forceful resurfacing of pent-up spiritual energies and emotional undercurrents.

The piece’s scale and liminal status as both a performance object and large-scale sculpture instigated a minor firestorm at the show. The artistic director Manfred Schneckenburger requested that it be kept away from the main installation grounds, so as not to interfere with his carefully-arranged curatorial concept, but Palestine pushed back on its initial placement at the edges of the festival. The bear required multiple subsequent moves owing to logistical conflicts, and at one point Palestine attempted to crowdsource a space for it through a plea in a local newspaper. At the same time, Documenta was peeved by the attention it received, given its size and photogenic nature. As Palestine tells it:

The day I arrived with a team of people to assemble it was the day when the national German television station was there to do the publicity for the grand opening. Manfred Schneckenburger . . . had chosen “invisible conceptual sculpture” as the theme. There was a one kilometre pipe made out of brass that Walter De Maria had put into the ground, so all you could see was a little circle. Scott Burton had some furniture that was hidden in bushes. So the television was all ready to do a big story on Documenta 8 and there’s nothing to see except my enormous bear. That night every television channel shows my bear which becomes the unofficial symbol for Documenta 8; and the curator goes out of his mind. 2

Indeed, the popular sculpture seemed to provoke a surprising response, at one point transforming into a de facto playground for juvenile attendees. Many visitors, including a nearby retirement community with denizens who had been children during Steiff’s heyday of 1906 to 1912, were inspired to bring their own childhood bears to view the work.

Despite the piece’s visibility and arrival into the final moments of the red-hot ’80s art market, it did not sell. After the closing of the festival, the sculpture traveled to Paris and Dôle, a commune in east France. The piece subsequently languished, uninsured, in a storage warehouse until Palestine one day received word that it had been mysteriously destroyed in a fire. A sad ending, but fitting given its epic aura. “God Bear died like Joan of Arc, he died like a saint: he was burned at stake,” he says. 3

From a certain lens, God Bear is a consummate microcosm of Palestine’s core sensibility, a unified but always shape-shifting set of artistic principles that he has been developing since his teenage years. Frank, mystifying, and misunderstood, Palestine’s totemic teddy seemed to embody many of the curious contradictions present in his entire oeuvre: sardonic yet reverential, distinctly American yet exotic, acutely personal yet universal, teetering between being a cause célèbre and a mysterious, ephemeral curio.

The fallen monument is just one realization of his broader project: Charleworld, a word that variously refers to his studio in Belgium, his sensibility, and a life-practice amassing six decades worth of activity into a single colossal work encompassing every piece the artist has authored, every concert he has performed, and every “orphaned” stuffed animal he has rescued. For nearly six decades, Palestine has set his efforts on practically every medium he’s been able to get his hands on, from electronic compositions made with early tone generators to videos shot on direct-camera portapaks, from painted fabric collages to massive room-sized installations. Charleworld channels his private obsessions, childhood fixations, and lifelong interests in religion, mythology, music, movement, and Gesamtkunstwerks into an expanding, total artform.

The eclecticism of Palestine’s work is owed in part to the diversity of inputs afforded him by mid-century New York’s cultural riches. His musical studies began at a young age, training in sacred Jewish choral singing with an eye toward becoming a cantor, and receiving instruction in piano and accordion. He was not yet thirteen when he started to gig as a percussion accompanist for the downtown coffee shop set, cavorting with the likes of Tiny Tim, Gregory Corso, and Allen Ginsberg. That same year, he got into the selective High School of Music and Art in uptown Manhattan, suffering through a three-hour round trip commute from Sheepshead Bay until the age of fourteen, when he convinced his mother to rent an apartment closer to his school. He was a precocious teen, who had an early love for Debussy and Ravel, and the stately abstract expressionism of Barnett Newman and Mark Rothko. Through an uncle who worked as a professional violinist and Lukas Foss, the father of a girlfriend, he got to sit in on Varèse and Stravinsky rehearsals, admiring the composer-conductors’ uncompromising leadership.

At sixteen, he began to frequent the West Village studio of choreographer and composer Alwin Nikolais, an early adopter of musical electronics who purchased one of the first Moogs; there, Palestine dabbled in synthesizer experimentation and produced his first electronic recordings. Meanwhile, he secured a regular job as a carillonneur at the bells of Saint Thomas on Fifty-Third Street and Fifth Avenue, a stint he maintained from roughly 1962 to 1969. He took a purposefully experimental approach, integrating disharmonious and lower-register chords, adapting works by Olivier Messiaen and John Cage for the instrument and eventually composing his own works, episodic musical narratives that he likened to daily soap operas. His unique playing style occasionally irked the more conservative parishioners, but he collected a coterie of key admirers: the president of CBS, whose offices were at nearby Fifty-Second Street, was a fan, and eventually invited Palestine to contribute carillon music to a broadcast news series; and the enigmatic composer Louis Thomas “Moondog” Hardin, who lived a block away, would often hang out by the church doors. Passerby Tony Conrad was so captivated by what he heard that he marched up to the belltower, and the two soon developed a close friendship. Later, Conrad introduced Palestine to his roommate Jack Smith, composers including La Monte Young and Terry Riley, and figures on the fringes of Andy Warhol’s factory such as Taylor Mead and Valerie Solanas.

To keep the Vietnam War draft at bay, Charlemagne became a perpetual student, studying at six different universities in eight years. He was promiscuous in his interests, taking courses in music performance, fine arts, and multimedia at Julliard, Columbia, New York University, and the Studio School. At the Mannes School of Music, he continued vocal lessons with the opera pedagogue Sebastian Engelberg, was exposed to Schenkerian analysis, and met the young poet and translator Jerome Rothenberg, who was preparing the materials that would become Technicians of the Sacred, a compendium of global spiritual rituals through the lens of poetics. Palestine was already nurturing an interest in indigenous sacred music and ceremonies—he was a diligent listener of Moses Asch’s Folkways Records, checking out discs from a Staten Island library, particularly falling in love with “the Polynesian and the aborigines’ and the Hopis’” songs 4 —but Rothenberg’s approach was a special revelation. Rothenberg had developed his interest in cross-cultural poetics while participating in downtown experimentalism with figures like David Antin, Jackson MacLow, and Dick Higgins; his appreciation for happenings, Fluxus, and conceptualism led him to consider rituals as a total form, carefully attending to the prospective meaning embedded in repetitive motions, shrieking, and trance states.

In the late ’60s, a “stoner roommate” who was a follower of Ram Dass encouraged Palestine to seek out Pandit Pran Nath, who had been staying on Ninety-Fifth Street with a pair of Dass’s students. Palestine, then in his early twenties, took regular lessons in kirana gharana singing and tambura, though he did not dedicate himself as a disciple, as had Young, Riley, Catherine Christer Hennix and others in the burgeoning new music scene. Palestine recalls that it was a sociologically enlightening experience, as it forced him to consider why a generation of white composers were finding themselves drawn to Indian religious music amid a decade of assimilation and secularization. “La Monte is a Mormon, Terry Riley’s an Irish west coaster, I’m a Jewish New Yorker,” Palestine reflected. “At that time we were very conscious of being a very un-tribal culture, meaning that we were all searching for a kind of identity . . . all was possible but . . . our own born tribal units had disintegrated into an American pablum, and so it was hard to say who you were if you were American.” 5

In 1970, Palestine briefly relocated to Los Angeles at the invitation of Morton Subotnick, joining the California Institute of the Arts faculty as an instructor. In the late ’60s, Palestine had been toying around with the synthesizers at Subotnick’s Intermedia Program on Bleecker Street in pursuit of what he called the “golden sound,” a pure and endlessly unfolding harmonic tone. On the West Coast, his search deepened: he became close with Don Buchla and Serge Tcherepnin, who were developing modular synthesizers, and asked the latter to help design a drone machine, which resulted in a series of reductionist yet harmonically complex compositions. “Two Perfect Fifths, A Major Third Apart, Reinforced Twice,” 1973, a demonstrative work from this period, unfolds just as its title suggests, although a twinkling set of overtones reveal themselves to careful listeners. Often, Palestine would design these compositions as long-form sound environments, lasting in the ballpark of six hours. “My pieces are like sculpture or large paintings—you can never see all of them,” he once told a music critic. 6

While at CalArts, Palestine collaborated regularly with the dancer Simoni Forti, whom he had initially met through the Dass and Pran Nath crowd. In late 1971, the pair performed Illuminations, a series of dance-rituals that harkened back to the two artists’ respective childhood interests in vocal music. They would trade off singing, and utilize miscellaneous objects including small bells, “glass harp” wine glasses, and a corrugated tube meant for connecting a stove to a gas source, which the artists referred to as a molimo. “This kind of collaboration between man and woman was uncommon at that time,” recalls Palestine. “Mostly other artists were doing very structural works while our performances were totally like we were on magicness drugs.” 7 According to Palestine, these were the first of his experiments with “body music,” a series of performance studies that exaggerated subliminal physical gestures, and they also marked the emergence of a stable of artistic signatures that would follow him throughout his career. A monkey dubbed “Pepperoni” given to him by Forti and a stuffed bear anointed “King Teddy” gifted to him by a girlfriend soon grew to be a posse of plush toys that adorned his piano, and Palestine himself would often doll up with showy hats and scarves, sipping brandy or chain smoking Indonesian cigarettes.

Through his travels with Forti, Palestine became acquainted with the gallerist and patron Ileana Sonnabend, who invited the pair to perform at the Festival D’Automne à Paris, and would soon become a key supporter of his off-the-wall activities. In 1973, she commissioned Four Manifestations on Six Elements (Sonnabend Gallery, 1974), his first record, which collected his sustained harmonic studies for drone machines and Imperial Bösendorfer piano, an instrument that he had fallen in love with while in California. The piano model, originally commissioned at the turn of the century by the Italian composer Ferruccio Busoni, suited Charlemagne with its extended lower register (ninety-seven keys, instead of the usual eighty-eight) and rich, precise timbre, which the composer would manipulate through rhythmic repetition. In performances and recordings—including Strumming Music (1974), released by the maverick Shandar label—he would keep the sustain pedal down and alternate between two tones a fifth apart, gradually adding additional intervals. Over time, the tuning would slip ever-so slightly, and a spectrum of hidden pitches would surface. As composer Ingram Marshall describes it, “After a while, the ear doesn’t distinguish between notes that are sounded by hammer and those which are harmonics, generated by the natural resonances of the piano and just appear because of the acoustical situation. Charlemagne, as he plays, is recycling what he hears into a kind of feedback loop, using his strumming technique to coax the dancing overtones out of their cover.” 8

Sonnabend also encouraged Palestine to explore video, a burgeoning medium among conceptual and performance artists, and arranged for him to play around with a camera and playback at the recently-formed art/tapes/22 studio in Florence. While visiting, he produced his first direct-camera performance titled Body Music I, 1973–74, in which he gesticulates like a shell-shocked patient, wanders through a bare room singing overtones, and flings himself against a wall. Throughout the ’70s, Palestine continued to produce a series of strange, ritualistic tapes: subsequent bodily investigations (Body Music II, 1973–74, and Snake, 1974), one-take explorations of a Coney Island roller coaster (Four Motion Studies, 1974) and a motorcycle journey across the island of St. Pierre (Island Song, 1976), extended portraits of private pathos (Andros: An Escapist Primer, 1975–76) and antagonistic monologues (Dark Into Dark, 1979).

Palestine was enjoying a robust presence at festivals in Italy, France, and Switzerland, while his piano concerts were becoming the stuff of legend in the New York performance scene. For a number of years, Palestine maintained a loft studio at the Idea Warehouse on 22 Reade Street, an alternative arts space where Philip Glass, Mabou Mines, and Ken Jacobs also worked, and he would frequently present extemporary recitals that combined his strumming technique, bodily experiments, and over-the-top monologues to stoke trance-like states in himself and the concertgoers. He would get drunk on cognac, and sometimes pour generous complimentary glasses for the audience to further inspire collective effervescence.

The presentations of this period often had a confrontational quality, an extension of Palestine’s twitching, chaotic, raconteuring stage persona that reflected his growing frustration with the buttoned-up new music scene. By the mid-1970s, many of his peers in so-called “minimalist music” like Glass, Steve Reich, and Young had started to garner significant institutional attention, while Palestine felt relegated to the status of footnote and simultaneously resented the whole framework. In occasional acts of frustration, he would try to shock the audience out of complacency using tactics that blurred the line between artistic subversion and personal bellicosity. At one notorious evening at Merce Cunningham’s studio at Westbeth, Palestine, bereft from the recent premature death of his brother and fed up with Cunningham and John Cage’s “bourgeois conservatism,” played a recorded monologue attacking stuffy avant-gardism and begrudgingly gave a four-minute demonstration of his piano chops, before spastically thrusting himself against the mirrored wall. The routine frightened the audience, including the New York Times dance critic Clive Barnes, who gave it a dismissive review.

Similar episodes continued. As Palestine would later recall, “around 1977 I became very . . . negative. I began to do things unconsciously that I didn’t understand, and they were very sabotagistic and I didn’t know what I was doing. I was pissing everybody off, I was breaking my bridges. I was hostile to people, I was doing performances and insulting people there—I was doing whatever I could to destroy whatever world I had created ten years before, without knowing, really, why.” 9 And so, for a mix of reasons including kicked ladders, shrinking opportunities, lack of recognition, personal turmoil, and reoriented passions, Palestine made a conscious decision to remove himself from the downtown context towards the end of the decade, and instead rededicate himself as a visual artist. Between 1980 and the mid ’90s, he rarely performed publicly and lived as an expatriate in Switzerland, France, and then Belgium. These were his years of wandering “exile.”

Palestine’s withdrawal from music culture at the turn of the decade prompted a new wave of works drawing on his iconographic obsession with mythical animals and plush toys. Between 1982 and 1989 he developed multiple exhibitions with the Eric Franck gallery in Switzerland that paid tribute to his spiritual affinity for discarded playmates, resulting in large-scale paintings, copper etchings, and a series of installations that arranged selections from his accumulating collection of stuffed animals into tableaus inspired by his love of Indian and Oceanic mythology. Across Palestine’s creations from this era, certain continuities reveal themselves: zig-zagging arrows, scribbled patterns and dots, and made-up and borrowed words or phrases like “pikli ahja poomoot” and “raakhk,” all comprising a cryptic, sacred language to be intuited by the viewer. Often, the pieces ascribe a waggish, anthropomorphic dignity to the animals, as in Hunter’s Alter Ego, 1985, a taxidermied cheetah staring into a mirror, reflecting Palestine’s own self-searching pathos of this period.

At the same time, Palestine was nurturing a habit of visiting second-hand stores—which he referred to as “orphanages”—and purchasing every forgotten plush toy on offer. “I’m using the throw-aways of our society to make sacred altars,” he once explained. 10 In the super-charged consumerist toyscape of the ’80s, this meant that media tie-in plushies like Mickey Mouses, Care Bears, and Looney Tunes began to appear in his art. The Smurfs, who Palestine particularly appreciated for their resemblance to Polynesian kings, had recurring cameos.

These collecting habits dovetailed with his formation of an ambitious, if short-lived, non-profit endeavor called the Ethnology Cinema Project. “It was a way of saving my life,” he later said of the project. “It was a period where I felt like nothing in my work was going well. I was lost but yet I loved all these lost cultures and I felt that all my inspirations, these people, were disappearing and only few traces were on film.” 11 At the time, he was living on the Hawaiian island of Moloka’i, the site of a long-running leper colony formed in the nineteenth century, and was immersed in Oceanic mythology. Conscripting his friends Louise Thompson and video artist Ken Feingold, Palestine had the idea to collect the vestiges of rituals, earmarking unearthed materials at the Bishop Museum in Honolulu and the Göttingen University repositories in Germany. During the research process, the trio discovered that the Smithsonian Institute was engaged in a similar reconnaissance mission, and ended up entrusting their findings to the archive in Washington D.C. and dissolving the project. Charlemagne’s pursuit of abandoned rituals, of both the sacred and profane variety, continued.

The construction of the God Bear and the relationship to the Steiff factory gave Palestine’s work a new, heightened sense of scale. The outdoor sculpture was one of several collaborations with Steiff, who custom-fabricated animals of Palestine’s own creation that fused mass-produced designs with attributes of deities; God Bear was itself based on the elephant-headed Hindu god Ganesh. Palestine had recently seen a wooden figurine of the god at a rug store in Cologne and been compelled to drain his bank account to acquire it. And although he was considerably frustrated by the fate of his Documenta monument, it prompted him to produce pieces that spilled out of the gallery context, such as La Caravane en peluche, 1990, a touring caravan of stuffed animals that the artist chauffeured around Europe.

A series of life events in the ’90s helped facilitate support for his increasingly sprawling creations. The 1995 reissue of Strumming Music on the Italian label Felmay spurred a critical resurgence of interest in the composer among record collectors, and a string of highly sought-after archival recordings were subsequently issued by labels like Staalplaat, Barooni, and Alga Marghen. After over a decade of relative reclusiveness, Palestine started to appear on festival rosters in Germany and the Netherlands, and he participated in collaborations with a younger generation of artists including the British industrial musician David Coulter, the German electroacoustic trio Perlonex, the Finnish duo Pan Sonic, and the French unit GOL.

In the late ’90s, Palestine met and married Aude Stoclet and relocated to Brussels, where he has resided since. After a comparatively restless period, his sustained life in that city has allowed him to maintain an expanding studio practice that houses his work, plush toy colony, a piano, and even a carillon, where he has since written and recorded new work. An abundance of space and time have allowed Palestine to metastasize every discrete aspect of his life into a total practice, mirroring in equal parts the role of ritual in pre-industrial societies; the marriage of architecture and sound found in instruments like the carillon, Bösendorfer, and church organ; and the Gesamtkunstwerks of mid-nineteenth century European aesthetics. The backdrop of the Low Countries, the birthplace of belltower belfries, only adds to the unified aura, as does the history of the family that Palestine married into: at the turn-of-the-century, Stoclet’s grandfather, Adolphe Stoclet, commissioned the construction of a Vienna Secession-styled mansion in which every aspect of domestic life would be designed, down to the silverware. Architect Josef Hoffmann led the project, and Gustav Klimt designed enormous mosaic friezes. “There are stained glass windows, piano, staircases, big enormous chairs and toilet seats; it’s all part of the work,” says Palestine. 12

It is perhaps worth noting that the Kunstgewerbeschule system, the circuit of German vocational art schools that helped produce totality-minded artists and designers such as Hoffmann and Klimt, was also the educational breeding ground of Richard Steiff; Palestine’s humble toy of choice and the Palais Stoclet were birthed from the same epochal moment. Palestine’s work from this moment further plunged the depths of the teddy bear’s endless emotional resonance: in Sacred Ooooo !!!, 1997, he photographed himself and his posse of stuffed animals posed in front of the graves of his relatives at a Long Island cemetery, and in D-Day P-Day, 2001, he restaged the Normandy landing with a cavalcade of 1,300 teddy paratroopers suspending from the ceiling, sly and heavy revisitations of both the personal and world-historical conditions of his birth. Elsewhere, he has suggested that his connection to his placeless, resilient, abandoned toy playmates draws from his family’s emigrant experience:

They are like refugees. Like my family, who came over in a boat. They tore up their papers before they came to America, so nobody would know where to send them back to. So they are part of the same story, but at the same time, if these beings are permitted, they will live long after we have gone. I imagine that they’re listening or something is entering their animist consciousness, and they will live for centuries. 13

The past decade has seen Palestine’s most ambitious installations come to fruition. This period of increased activity and visibility in the American art world began roughly with his inclusion in the 2014 Whitney Biennial, for which he decorated the Breuer building’s staircase with a selection of divinities and piped in a recording of himself running up and down the stairs and chanting. A string of monumental exhibits followed: “GesammttkkunnsttMeshuggahhLaandtttt,” an immersive retrospective, was presented at Kunsthalle Wien inVienna and the Witte de With Center in Rotterdam in 2015. It featured a blueprint proposal for the God-Bear Museum, a speculative institution that could fully accommodate both visual and performing arts, more thoroughly wedding life and art. In 2017, the Jewish Museum in New York commissioned “Bear Mitzvah in Meshugahland,” a homecoming installation in part an homage to the teddy bear’s Brooklyn roots. At the now-defunct alternative arts space 356 Mission in Los Angeles, the artist presented “CCORNUUOORPHANOSSCCOPIAEE AANORPHANSSHHORNOFFPLENTYYY” in 2018, drowning monitors playing his early video work in a sea of plush animals, and draping tapestries of stuffed toys, boatloads of Beanie Babies, paratrooper teddy bears, and mischievous disco balls from the warehouse gallery’s high ceilings.

But it’s possible Palestine’s most massive accomplishment is his studio itself, the hangar-like space that he’s dubbed Charleworld, which not only stages his creations in progress, but also acts as a repository for the vast majority of his oeuvre. “My works have been so neglected financially that I own almost 90% of [them],” he has noted, with resignation. “I have decided I will never sell them for little amounts, they will only be sold as masterpieces, so we can be sure that they will be treated as great.” 14 Overflowing with a fraction of the thousands of stuffed animals he has taken in, his workspace has come to double as a living archive, self-funded museum, misfit island, and late-style masterwork of visionary art. The artist’s expressionistic painting exercises from the ’70s commingle with collaged bouquets of scarves and toys, a sea of orphaned plushies gather around a self-portrait statue, and a free-standing carillon and a Bösendorfer piano stand in wait for when inspiration strikes. For Charlemagne, these multifaceted artistic activities—his painting, arranging, fabricating, sound-making, running, jumping, singing, bell-ringing, kvetching, et cetera—are all one thing, and it’s been his Sisyphean mission to convince the rest of the world of such. Call it the golden mean, the great spectral continuum, the God Bear: a Palestine concert or artwork is a momentary window into his vision of the elsewhere, a sanctorium on wheels, in which his thrift-store animism can summon subterranean forces out of a single tone or discarded plaything.

Installation views of CCORNUUOORPHANOSSCCOPIAEE AANORPHANSSHHORNOFFPLENTYYY, 356 Mission, Los Angeles, 2018.