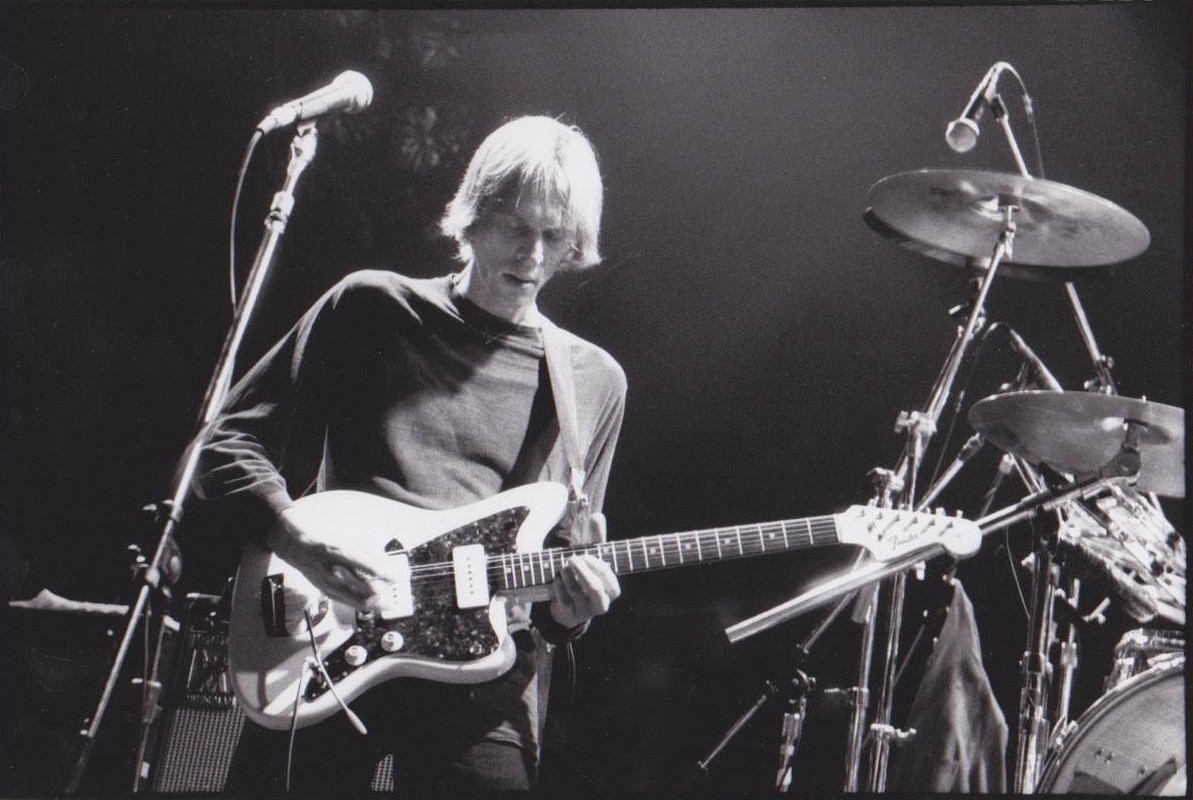

Tom Verlaine in 1977. Photo: Godlis.

A guitar hero for people who are embarrassed to have guitar heroes, Tom Verlaine came to prominence in the ’70s CBGB punk scene with his band Television, yet his work seems almost diametrically opposed to the stereotypes associated with that era and subsequent punk. Under Verlaine’s stewardship, Television was notable for exquisite guitar interplay (between Verlaine and Richard Lloyd) and longer group improvisations, more so than virtually any other band of the era, save the Patti Smith Group. In this way, they really effected “alternative” rock in the purest sense—music with a different set of values than contemporary arena rock. Television carried over some of the same qualities of the ’60s music once heard on both AM and underground FM radio, but built on them in a different way—more esoteric, and introspective—than did prog, glam, and heavy metal. I tend to the think of Television as somehow analogous to cult film director Terrence Malick: both made two rapturous, visionary classics in the ’70s (the two albums on Elektra, Marquee Moon [1977] and Adventure [1978], and the films Badlands [1973] and Days of Heaven [1978], respectively), disappeared from sight in the ’80s, then reappeared in the ’90s with comeback efforts (the former with the 1990 LP Television [Capitol] and the latter with The Thin Red Line [1998]).

Verlaine launched a solo career in 1979, and after a few albums of rock songs he made an influential instrumental record, Warm and Cool (Rykodisc, 1992). By the late ’90s he was doing live instrumental music for silent films; I previewed one of those shows, at St. Ann’s Church in Brooklyn, for Time Out New York, writing that “the author of such Television classics as ‘Marquee Moon’ and ‘Foxhole’ doesn’t seem to have much interest in writing songs these days, and who can blame him?” I heard through the grapevine that someone had shown Tom the preview and that he liked it. After 9/11, Tom and Sonic Youth joined forces to do a benefit at the Bowery Ballroom in Manhattan, and he needed a second guitarist; Thurston Moore recommended me, so Tom called me up and I played the show, with Television’s Billy Ficca on drums. A couple of years later, Tom tapped me to do liner notes for the remastered reissues of the first two Television albums, and in 2006 I wrote a cover story for the Wire timed to two simultaneously released Verlaine solo albums on Thrill Jockey, Songs and Other Things and Around. Thrill Jockey wanted Tom to tape an inter- view for European radio in advance of his tour behind the records, and he chose me to do it. Sue Garner, my old Run On bandmate and a Thrill Jockey recording artist herself, recorded the interview at her studio space in Greenpoint, Brooklyn.

Alan Licht

ALAN LICHT: The one thing that I haven’t seen anybody else ask about these two new albums is where their titles, Songs and Other Things and Around, came from.

TOM VERLAINE: The title for the vocal record [Songs] came from not wanting a concept laid over it all—in other words, not wanting an idea or a story line to it. So that became Songs. And then I thought, “Since there are instrumentals on it, too, I have to say something else,” because then people start saying, “Well, it’s not songs, there’s instrumentals”—so I added Other Things. The title for the other record came from looking at the picture [on the album’s cover], which has a semicircular train track, and the idea of the jeep going around something, and also the idea of a pun on the word squares—the old beatnik term squares. The term in the beatnik era was, “Oh, that’s so square,” but they never used the word round. It goes back to this book Flatland [1884, by Edwin Abbott Abbott]. This was this odd book of ideas, where the whole idea of squares as unhip people came from. People that were round were whole and energetic and positive, and things that were square were not. Flatland, as I remember—I read this as a teenager—was a crazy combination of theory and almost poetry. . . . But the idea of “rounds” never showed up in the society of the 1950s—

AL: [Laughs.] Or since.

TV: —just the idea of squares [laughs].

AL: Although, the roundheads—that was Cromwell-era England.

TV: Also the idea that a round house was the ideal architecture—the Indians with the teepees, that things should be in the round.

AL: Crop circles—there’s a whole mysticism around the idea of circles. Circle dancing, too, like the Shakers.

TV: Oh yeah. Shaker circle dancing. I’ve never seen anybody do this—actually, I’d love to see that. There must be a film of it somewhere.

AL: I only know the engravings of it.

TV: The engravings are great—they’re really, really cool. Some of the songs are really beautiful too. But I wonder what the dance was. I mean, the people were falling out in that dance—it was an ecstatic thing, it wasn’t just a social thing. I think the last Shaker woman was in Maine. I read an interview with her in the ’80s—she was like ninety-six years old. I went up to see the community. There’s just a few buildings in the valley; there’s a shop there selling some things. Maybe there are some Shakers alive, I don’t know.

AL: There must be some descendants, some renegade Shakers—

TV: Renegade Shakers who propagated and left the cult, as it were. The music is very good.

AL: It’s cool that the Songs album starts and ends with instrumentals, because it makes a transition between the two albums where you can listen to them in either order if you have both of them, making a bridge between the two. Was that something you had thought about it, making the two albums a pair that way?

TV: It was something I thought about when I went to do a vocal on the first track, and didn’t really get anywhere with it, didn’t like it. I took what I had done off of it and just realized the song doesn’t really want a vocal— it sounds kind of nice the way it is. I think there’s a little bit of a history of people doing these instrumentals first [on an album]. There might even be a Beatles record, but even that might have some la-la’s on it. What’s the first cut on the Magical Mystery Tour [Capitol, 1967] record?

AL: I think it’s “Magical Mystery Tour,” although there is an instrumental on that record [“Flying”]. The first Neil Young record starts with an instrumental; actually, both sides of that record start with an instrumental.

TV: Ah. That record, I still don’t think I know it. . . . The instrumental last track on the vocal record [“Peace Piece”] was this thing I had done in some- body’s apartment where he had a lot of nice, really big tube limiters and interesting ’50s gear, and actually nice microphones as well. I’ve always liked recording in apartments, so I thought I’d make something in there. I totally forgot [the track] existed, and then when I went to master the record I thought, “Oh, there’s that thing,” and then I mixed that in five minutes and put it on the end. I’ve since been told there’s another recording called “Peace Piece,” which I guess is a Bill Evans solo piano composition. Curiously, a day after a journalist from Sweden told me about this, I was in Starbucks and heard this really great piano piece, and I asked them what it was, and they said it was called “Peace Piece.” Very spacious, very nice piece. So now I have to try to change my title [laughs].

AL: “Peace Piece 2,” “Peace Piece Jr.” [laughs]. Where did you find the guys who are playing on the record, besides the guys you’ve used before?

TV: Well, Jay Dee [Daugherty] was in my touring group after Patti Smith took a break in the ’80s. The drummer, Lou Appel, came from the recommendation of a studio engineer as a guy who was extremely fast in learning things but who was also kind of sick of doing rock stuff. I think he was doing Southside Johnny or something and he wanted to do something different. The other drummer, Graham Hawthorne, came from a guy who had worked on David Lynch soundtracks. He’d done a lot of really oddball stuff, but had actually grown up in Chicago playing really hard-core funk music, and he’s really adept at playing oddball beats. That song “The Day on You” was a jam session in which I said, “Do you remember this sort of early-’60s New Orleans thing? Let’s try that faster.” And he would just start playing these things that were really, for me, great, because there’s not a lot of drummers who can play that style of stuff and play it really enthusiastically. So that was about a ten-minute jam session that I just edited and put the vocal on. It’s kind of unusual, because it’s almost like a folk-strummy rhythm guitar against a very weird beat.

AL: And Billy Ficca is playing on these records—you’ve been playing with him since high school, right?

TV: Playing with him since ’66, probably, in garages in Delaware. The great thing about Billy is he doesn’t care if you rehearse or not—you just sort of throw an idea at him, like, “This is sort of up-tempo, and let’s not use the hi-hat,” or, “This is kind of tom-tom thumpy Haitian music” [laughs]. And he immediately plays something that’s suitable. And he plays it well. And he plays it in one take. He’s actually much better at that than he is at learning a song [laughs].

AL: Did you guys have similar influences growing up?

TV: We both liked jazz. When I first saw him play, he was playing with some guy from Chicago who was a lot like Charlie Musselwhite—this hard-drinkin’ white guy playing blues harp who was absolutely amazing. I never heard his name again and can’t remember his name. He was just passing through and they were playing a church basement concert [laughs]. There were about eighty people there to see this blues thing—totally traditional, Muddy Waters electric blues stuff. Billy was playing drums, and I thought, “Gosh, this guy plays great.” He has a liking for any sort of music, and he gets the spirit of it right away, I think. And if you want something played really lightly, he’ll do it and not screw it up. He’ll play light and won’t suddenly hit something so loud that it breaks your mic—he’ll play the whole thing light.

AL: Have you been a big Middle Eastern music listener, or Indian music listener? Because there is stuff on these albums that point in those directions.

TV: I wouldn’t say I’m a big listener of that. I kind of get the idea of it and I don’t even have a lot of records of that stuff. I know one really great record of an oud—I don’t remember the player’s name. I think he was from Iran, and it’s probably an early ’70s record. I think the thing about playing music that, for better or worse, has that flavor—it just comes from picking a scale. If you’re tired of the Western scales then you pick a scale with different intervals and improvise on it. For me it’s a challenge because I’m not really fluent in that, so it slows me down, but it also immediately lends a different mood to things, I think. The other way to do it is just to change the bass note and play a regular Western scale [laughs]. Have your bass play a C but start the song with the guitar on a B and you get very odd things going.

AL: Was [John] Coltrane stuff like “India” something you were listening to back when it came out?

TV: I can’t remember that record. I’m sure I had it at one time. Coltrane in general—of that period, Coltrane, [Albert] Ayler, [Eric] Dolphy, and Ornette Coleman, I probably liked Ayler the most, who is probably the least modal of those, strangely enough. And also Dolphy, as a soloist, I probably liked a lot more than Coltrane or Coleman even. The thing I really liked about the Coleman records, when I remember them now, is the Scott LaFaro bass stuff and the Eddie Blackwell drumming. I’ve been trying to find Eddie Blackwell’s drum kit. In the ’70s someone said he had made his own drums—he was fed up with drums you could buy. For years I thought I should look him up and go in and play with him for a while. I never got around to it. I don’t know where his drums are now, because he’s passed away. . . . I wonder if that was a true story, that he had made his own drums. But his drums definitely have a certain sound on those Coleman records, the way they’re tuned.

AL: I saw him play with somebody and it didn’t look like it was a customized kit—

TV: Probably something they had rented for the gig . . . Another New Orleans drummer, actually.

AL: Is that where he grew up?

TV: Yeah. Knew all the parade rhythms and all that stuff.

AL: And you’re really into Chris Kenner and [New Orleans] stuff like that.

TV: I really like Chris Kenner’s stuff—I mean, there’s not much of it. That goes back thirty years. When I first was in New York, I was at a flea market and this guy had a box of 45s for five dollars, and it was all New Orleans stuff that I hadn’t really known. Lee Dorsey, things like “Working in the Coal Mine,” those kinds of hits, but there were also these twenty-five other singles that I’d never heard or seen since, which had much more quirky rhythms and oddball guitar things. I’ve since read that Allen Toussaint wrote out every note for the bass players and drummers. You had to be classically trained, and the guys he used over and over on all those sessions were sitting there reading music. And the guitar player was a seventeen-year-old kid who’d be going chink, chink-chink through the whole thing [laughs]. That the rhythms, especially the bass stuff, were charted is really surprising—that it was approached as this written-in- stone music. You know, play it until it’s right, play it with no mistakes. There it is in front of you; that’s what you play. It wasn’t like, “Let’s get a groove going, guys,” or something.

AL: There’s some stuff from New Orleans which is super sloppy like Huey “Piano” Smith—

TV: Mm, yeah.

AL: —but the stuff on the Chris Kenner album—

TV: That’s all Allen Toussaint stuff.

AL: —there’s almost like a trance element to it, which, like [Steve] Reich or [Philip] Glass, is very precisely played.

TV: But unlike Glass and Reich it’s not just streams of eighth notes flowing by. It’s very, very—it’s absurdly syncopated, actually. A lot of it is things that no drummer would ever think of to play when sitting down to play dance music. It doesn’t really, to my ears, make people want to dance, but when it’s all together it somehow creates some kind of weird, itchy thing that, I think, only in New Orleans people used to dance to this stuff. If you listen to the so-called club music, or funk music from the ’60s, it’s not quite like that. Some of James Brown gets into that stuff, too, but . . .

AL: Have you been to New Orleans much?

TV: I was only there once, for one day, in ’85 or some- thing. It had an interesting atmosphere—you really kind of had to watch yourself. This local guy took me around to all the after-hours clubs, and they were really cinematic scenes. You would go into a club with a couple of purple bulbs, and it would be twelve barstools and two small tables and it would be packed, and some half- naked girl would slink next to you and rub on you next to the bar. The guy who was with me was nudging me, saying, “Don’t get close to that—her boyfriend’s in the corner.” And you look in the corner and it’s this murderous face, with scars [laughs]. You don’t know what’s going on there—it’s really strange and slightly sinister. Unthinkable stuff like you’ve seen in some crap movie would be completely true to life there.

I remember when I checked into the hotel, I went into my room and there was a bone on the pillow. This strange bone [laughs]. I said, “What is this, some strange voodoo trick from the maid or something? Why is there a bone on my pillow?” So I went down to the desk and I said, “Is the maid around?” They said, “Do you need something?” “Nah,” I said, “there’s a bone on my pillow.” It became this big discussion. They said, “Oh, just a minute.” I didn’t hear anything that went down. And then it was like, “Do you have the bone?” And I said, “No, I threw it in the river,” and they said, “That’s a good place for it” [laughs]. I thought, “This is so bizarre, there’s a bone on my pillow.”

AL: [Laughs.] Not a mint, but a bone.

TV: Yeah, exactly. I asked everybody else on the tour, “Did you have a bone on your pillow”? They said, “What are you talking about?” [Laughs.] So who knows what that was about.

AL: Do you read much hard-boiled fiction or see film noirs? Sometimes people compare your music to that sort of thing.

TV: I read that stuff in the late ’60s. I read probably all of Raymond Chandler—but that’s like real poetry, those books. They were unique in my experience. [Mickey] Spillane was actually pretty interesting. Spillane I know for a fact was a huge influence on Patti Smith’s writing—this extremely staccato, short stuff. But Spillane’s books tend to be all alike, more than Chandler’s. That whole era, in my childhood, of black-and-white films with lots of shadow, tough-talking guys, all that kind of atmosphere, probably had some effect. I couldn’t specifically say what [laughs]. Even more so than that, I remember being terrified by really trashy science-fiction films in the ’50s. They didn’t show a lot of those on TV, but occasionally one would come on. There was one called When Worlds Collide [1951], which is actually, I think, in color, and it was about this planet moving closer and closer to the earth, and it was going to burn the earth up, but only one hundred people could leave in these spaceships. It must have been before the age of seven; child specialists say that before the age of seven kids can’t tell the difference between language and deed, so if a mother says, “I’m going to kill you,” it’s like the worst thing a mother can say to a kid because it’s like the kid experiences being killed, and he doesn’t know what that means, really, either [laughs], except that it’s terrible. But for months after this movie I thought the sun was getting closer to the earth. I would go outside in the day, and you can’t really look at the sun, but you think, “God, it’s getting hotter” [laughs].

AL: Here it comes!

TV: I would look out at the moon at night, and the moon was getting more and more full, and I thought, “Oh gosh,” and I would ask my father about the space- ship—“Is the spaceship gonna take us?” And he’d go, “No” [laughs], “what are you talking about?” For weeks I was really scared, and then I think my father realized I had seen some movie or something and told me, “Don’t worry about it” [laughs].

AL: Have you ever met any of these directors? Did you ever meet Nicholas Ray?

TV: I met Nick Ray because the kind-of-patron of Television in the ’70s, Terry Ork, was a film expert and had some connection with Nick Ray. So he said, “Well, I’ll bring Nick to the rehearsal,” so he came down to this rehearsal. He was a giant guy, like six foot six with a patch over his eye. I think he was drunk even when he got there. He had his girlfriend, this very devoted younger woman who helped him out on many things. I think he gave us a quote we could throw on our poster; I don’t know what the quote was, but it was kind of meaningless, because nobody knew who Nick Ray was. It wasn’t like getting a quote from Bob Dylan or—

AL: I think I remember that—it was something like “These guys are tough as nails, they make me cry.” At that point I don’t know if he was living in New York or still teaching at Harpur College [at SUNY Binghamton], but he was spending a lot of time in Times Square.

TV: Really?

AL: Yeah. There’s this great collection of his writing [I Was Interrupted (1995)] and transcriptions of some of the classes he taught upstate, and his wife [Susan Ray], who you’re talking about, did this long introduction where she talks about what his life was like in the ’70s.

TV: I think he was ill for a very long time.

AL: He was. That movie, Lightning Over Water [1980], that Wim Wenders made, documents him in the last couple of years of his life.

TV: I finally met Wenders last year after some show. I wish he wouldn’t use pop people in his movies, though.

AL: Like Nick Cave?

TV: Yeah, I don’t think these people are so wonderful in movies, really. That’s just my opinion. Real actors are people that are somehow inspired or passionate that seem to be much better than some rock singer just waltzing through. I like the way Alan Rudolph would use Neil Young as a gas station attendant for a minute, or Tom Petty as a parking lot attendant—that kind of thing makes more sense to me.

AL: Bowie in The Man Who Fell to Earth [1976] . . .

TV: Yeah, I mean what is that? That’s just a context, isn’t it? If you say somebody’s an alien, you’re going to think they’re an alien through the whole film no matter how they act [laughs]. The context becomes the act and you become a successful actor, in a way. It’s like The Elephant Man [1980], the same thing. The appearance does the whole thing, so you could say your lines as a joke and it would still have a pathos to it. I should get some roles like that. I could play a vampire. I wouldn’t have to do anything—the role would be so consuming [laughs] that it would be believable.

AL: So how many sessions did it take to record these records?

TV: [The] instrumentals was two nights of recording, and a third night of editing, and erasing mistakes, and then the fourth night was overdubbing background things, maybe some organs . . . I don’t think there’s any feedback drones. Adding some guitar parts here and there. Maybe there was a fifth night, mixing and remixing some things. And, actually, when it got to be mastered I ended up doing even more editing—a lot of the cuts were a lot longer. On the instrumental record as well, I wound up shortening them. They just seemed to sound better being more succinct. The vocal record was a couple of years of recording but only a day or two every third month [laughs], so it would be calling up the drummer who was in town that week and saying, “Are you available Thursday and Friday?” And that would be it for January; in March or April, doing the same thing again. And often those sessions would produce maybe three usable tunes, of which I would pick two or maybe even one. When I had a collection of eighteen things or more together, I decided to use maybe fifteen or fourteen and then started editing those and overdubbed on them. So the maximum amount of days—I don’t know, maybe it got up to forty days to record and mix that whole record. I’d still be mixing it if I had my way—it seems to take forever to mix things. I always hear, when a record’s out, how much better a mix could be, and you wonder why you didn’t hear that at the time you were mixing, that kind of detail. But it seems to have everything to do with the vocal. Once the vocal’s out of the picture it seems to be really simple to balance instrumental music—but with the voice, for me it gets a lot more complicated.

AL: In trying to see where it’s going to sit.

TV: Right. Most people seem to like loud vocals. I hear pop records that I like, and I realize when I’m hearing them that the vocal is twice as loud as everything else, but if it sounds good . . . But I tend not to do that myself. I tend to pull the vocal back.

AL: If you go back and listen to the Rolling Stones’ records of the ’60s, and other people too, the vocal is nowhere near as far out front as it is on a lot of stuff today.

TV: And it could be that those were the first vocal records I heard, so that’s what’s in my sound-picture of a way something should sound. I do like the way those records sound. People sang farther from the microphone back then, too—no one would be up on the mic. Julie London would be up on the mic—in those early days, I think she was the first singer who was told to sing within an inch of the microphone to get that kind of intimate thing going.

AL: Was this done in studios, or home recording?

TV: Ninety percent of it was done in studios. Fred Smith, the bass player—we did some guitar stuff in his house, and some editing and a little bit of vocals, and the last piece on it was done in an apartment. I like the apartment recording situation. The more I do it, the more I like that. I can’t find an apartment for drums yet, though.

AL: [Laughs.] That might take a while.

TV: When I lived on East Eleventh Street we decided, “We’ll rehearse in the apartment” [laughs], and it was less than twenty minutes—there were cops at the door. And that was the end of drums in an apartment.

AL: Have you ever had a four-track cassette recorder or something like that?

TV: No, the most I’ve ever had is literally a twelve- dollar Radio Shack cassette thing, which is like a note- book. I get an idea, sing it in there, talk it, or play it in there. I very rarely listen to them again. When I had broken my arm in the mid-’90s I remember listening to dozens of cassettes, most of the time thinking, “Why did I record that little thing? It wasn’t very good” [laughs]. There are a few things on there, a few minutes of this and that, that wound up being made into songs, but not as much as I thought there would be.

AL: Do you write down chord changes when you’re working on stuff before you go into the studio?

TV: Yeah. Well, the easiest way for me to record is one guitar, bass, and drums, and so I go through it real quickly with the bass player and drummer while some- one’s setting up the mics, and throw a chord chart on the floor for the guys and then experiment a little bit. Like, maybe the A chord on the guitar doesn’t want an A on the bass, maybe it wants something else, that kind of idea. Or in the instrumental record it would be picking a scale; each scale or mode has a name, but I’ve never been able to memorize them, so I’ll just say, “This is the scale, but let’s use that note for the bass and move it around here or there,” that kind of thing. Or hum a bass line.

AL: You produced all your own records, right?

TV: Yeah—I mean, in the early days, on Marquee Moon, I didn’t even know what a producer did. I started listening to records and I didn’t know what an engineer did as opposed to this or that, and Fred Smith again played me some Rolling Stones and Led Zeppelin—there was this key pile of records that all seemed to be done by Andy Johns. I thought, “Well, we don’t sound like any of these people, but I guess these are good-sounding records” [laughs], “so let’s get that guy.” We somehow found him in his apartment, he was living in LA, and he was a real riot—“How the hell did you find me? What do you want me to do?” [Laughs.] He said, “Well, OK, I’m not doing anything around Christmas—I’ll come to New York.” He had no clue what we were doing. He also had an enormous appetite for alcohol; the first night it was two large bottles of wine and a case of beer. He came in with this under his arm, a shopping bag with wine and a huge case of beer [laughs]. We were playing within two hours—he was really fast. And he would pull me out in the hall: “What kind of music is this? Is this a Velvet Underground trip? What is this, is this New York subway music?” So that went on for about ten days, and then he said, “Well, I guess you don’t really need me, I’m going back to LA tomorrow.” So we did the overdubs with the tape-op guy, who was actually a decent engineer, and then we had to beg him to come back to mix it. He came back right around New Year’s to mix it, and suddenly, I guess, he heard what we were doing or he had an ear for it, and he said, “Ah, I see what this is, I see what this is.” He became really enthusiastic in mixing it. It turned out well. It was probably one of the five oldest studios still working in New York at the time. It had a board with tubes, with the valves, which gave it a kind of sound. And there was no equalization on the board, and there were no compressors, so it was this very basic kind of thing, which he was really mad about when he saw it—he thought, “What are you working on here, a World War II recording desk?” [Laughs.] “This is crazy.” It was at A & R, a room that Phil Ramone had built for himself, so they didn’t rent it out much. I think Dionne Warwick records were made there. It wasn’t a giant, spacious place but it did have a nice sound. The reason I liked it was that it looked like our rehearsal loft—it was a bit sloppy and not gigantic, but easy to work in.

AL: Have you ever gone back since, now that you know what a producer and an engineer are [laughs] and gotten interested in specific producers and engineers from records?

TV: There were records where the sonic quality really hit me. I remember late ’70s, early ’80s, hearing a Cars record. I actually heard it in England—someone from our record company was driving me somewhere and this thing came on, and I thought, “Jesus, this thing sounds amazing”—the song didn’t do anything for me, but just the sonic quality of it was really amazing. And she said that [it] was produced by this English guy who had done these Queen records, and Queen were probably in my top three most despised groups of all time. I thought that this opera showbiz, and the fact that people liked it, was a real bad sign for guitar music, and the vocals as well. Anyway, so I thought, “Well, that’s interesting that the guy who did that could also do this little, dinky Cars sound but make it so explosive sounding.” So I started to have an ear more for engineers and what things do, and the different types of gear.

AL: That was Roy Thomas Baker who did the Cars and Queen; Jim O’Rourke is super into him.

TV: Yeah. There’s one great Roy Thomas Baker record—I don’t know if I talked to O’Rourke about it—I found this thing in a thrift shop. I don’t know if he produced it. I think it was one of the records he engineered before he decided to become a producer. It was some English singer, very pop, but again an explosive sound. I sort of learned everything that that guy did through grapevines of things and other engineers in the early ’80s, and I decided my Roy Thomas Baker record was going to be Words from the Front [Warner Bros., 1982]. That was actually all Roy Thomas Baker techniques, but of course not those guitar sounds, and not giant rooms for explosive drums, but very much an overload sound of pushing not the board amplifiers but the tape compression. Then I went to mix it and totally hated the way it sounded [laughs], so we would try to find little tracks that had gotten recorded by accident. We found a drum track where there was a mic on that was very low level on tape—in other words, not compressed and not distorted—and we would use that for the main drum mic because it sounded normal. We had to try to undo all this crazy tape compression stuff. I think it’s very good for distorted guitar, if you’re pushing the limits of tape; on things that are already somewhat distorted it’s good, but for other things it’s not really so good. I’ve gone back to liking Rudy Van Gelder sounds—not so squashed, put a microphone in front of it and leave it alone kind of sound.

AL: Have you gone in to do other records with specific ideas like that, about a certain way to produce them? I remember reading somewhere that for Dreamtime [Warner Bros., 1981] you put tape on the VU meters so no one could see what the levels were [laughs].

TV: Yeah, that was a thing in the early ’80s. I remember the engineer was recording the first day, and I said, “Look, don’t look at the meters.” He said, “You’re crazy.” I said, “Let’s just not look at the meters.” So we would do this, and I would say, “Don’t look at the tape machine meters,” and just record it and play it back. And we did this, and the meters—you don’t know where they were, because they were so far into the red. They could have been not just plus ten, they could have been plus forty. You don’t know where they were, but the distortion didn’t sound bad, so we just let the thing go like that. On that record it seemed to work better than on Words From the Front. But the guitars are a little more distorted on that, too—things are pushing more in a different way. That record was also one microphone for everything—we had one old German microphone, I think a [Telefunken] 251. I don’t know why we loved this—we used it every time we dubbed a guitar or vocal or anything. I don’t know how wise that is, in retrospect—I mean, that record sounds very loud. I play it every couple of years just to see how good or bad it is. It’s very low-mixed vocals with very loudly recorded instruments—it has a certain thing to it.

AL: Was there a production idea you came in with for these two new records?

TV: Yeah, the new stuff was much more back to the old school. By 2003 or 2004 I had found the microphones I liked, basically these ribbon mics that are, again, I think, German: a Beyer ribbon mic and a mic from Denmark, a B&K. Just really high-quality mics and minimal processing, dumping it onto tape. So there’s not a lot of complicated engineering or concepts of recording going on—it’s the right microphone and the simplest way to do it.

AL: Although there’s one track where there’s some kind of processing on the drums.

TV: There’s really heavy processing on the track called “Documentary,” because it was recorded in a really bad studio on a really bad desk. . . . I dumped that one into a computer right away, so it has a lot of digital-type recording on it, as opposed to the old tape thing on it. I think that’s the only one on the record that’s like that. There’s a little bit of that on “Day on You,” too, I think—those drums needed some real help. Because, again, it was very quickly recorded in a room that I only recorded one day in. I wasn’t quite sure what it was going to sound like. But the drummer played well. So . . . you work with it.

AL: There’s also things about record pressing and mastering, too.

TV: Yeah, that’s true. That’s a whole science that’s probably dying out because there’s so few mastering people that know how to do vinyl now. It’s disappearing.

There was a guy in Nashville who’s been mastering vinyl since the ’50s, and he says now he had to get computers because all the rap guys who want the vinyl send him a file, so he had to learn computers. And everything has to be loud—the digital file of the music is insanely loud, squashed, and then they want the vinyl to sound even louder. And vinyl has real limits with volume, especially in the bass. When I went to master a record in ’81, I went to the guy and he’s rolling off loads of low-end, 40Hz deep bottom, and I said, “What is this?” And he said, “Yeah, this is what the disco music does.” I go, “What are you talking about?” He says, “You go to a club and you think you’re hearing all that big bass, but it’s the sound system. If I had tried to cut these records with the bass that people wanted it would just rumble the whole club.” So the bass, where you think it’s that deep thing of 50Hz or something, is really like an octave higher, like 100 or 200.

Somebody once played me a Beatles record which was a safety copy of Abbey Road, and the bass was like—I guess McCartney was the one who was always around during the mixes and saying make the bass louder, but the bass is so loud on the original Beatles tapes, it’s insane. It’s like reggae music, it’s so loud, and the joke was that when the Beatles handed things in to master, all the cutting guys immediately plugged in this thing called a low-pass filter and had to dump tons of low end, because if you tried to cut your vinyl with that kind of low end you wouldn’t hear anything but bass, and you’d have to bring the level down so low. You never think of Beatles records as bass, although they have great bass playing. The tape I heard was just insane—it was like an insane person mixed it, put the bass on ten and then everything else on four. It was very funny.