Pandit Pran Nath performing at Indira Gandhi National Center of Art and Culture (recording for the archive there), Delhi, with Rik Masterson, Terry Riley and Shabda Kahn (left to right). February, 1994.

This interview took place by phone in the summer of 2001, while I was working on a profile of the Hindustani classical vocalist Pandit Pran Nath for The Wire. Through La Monte Young and Marian Zazeela, I made connections to a number of musicians and composers who had worked or studied with Pran Nath, including Terry Riley, Jon Hassell, Charlemagne Palestine, Henry Flynt, and Catherine Christer Hennix. I didn’t know who Hennix was at that moment, but I was blown away by what she said to me, and I quickly understood that I was talking to an exceptional person.

Pran Nath was born in Lahore, Pakistan, in 1918, and studied with the great Kirana gharana master Abdul Waheed Khan. For a time Pran Nath devoted himself entirely to singing and praying in cave in the Himalaya, before teaching singing at Delhi University. La Monte Young heard home recordings of Pran Nath made by Shyam Bhatnagar, in the 1960s, and invited Pran Nath to America in 1970. That same year, Young invited Hennix, who was living in Stockholm and making electronic music, to meet Pran Nath at the Nuits de la Fondation Maeght event at St. Paul de Vence in France. Hennix became a disciple of Pran Nath’s in 1973, and assisted him with the course he taught at Mills College in the 1970s. Pran Nath died in 1996, but Hennix, along with Young and Zazeela and many other students, remains devoted to his work. When I called Hennix in 2001, she was working with the dissident Russian mathematician Alexander Esenin-Volpin in Cambridge, Massachusetts. It was around this time that she began making computer based musical compositions after a ten- plus-year hiatus. The “solitone” drones would become the basis for her work with her ensemble The Chorasan Time Court Mirage and for her return to solo keyboard performances in the style of her classic 1976 piece The Electric Harpsichord. Her recent ensemble and solo performances both involve raga-like structures related to those she learnt from Pran Nath. While The Electric Harpsichord focuses on her relationship to Pran Nath (which for her remains the core of her musical life), it also gives a wonderfully clear picture of how she views the powers of music, sound and vibration, and what it means to live a life devoted to the full manifestation of those powers.

Marcus Boon

I.

MARCUS BOON: How did you first meet Pran Nath?

CATHERINE CHRISTER HENNIX: I first met him through La Monte Young. My first encounter with [Pran Nath] was in 1970 at Nuits de la Fondation Maeght. I heard him tune the tamburas and it just blew me away. I’d heard tamburas many times before, but not on that level. I don’t know if you’ve heard recordings of Indian music from the ’50s and ’60s. What’s most remarkable about most of those records is that the tambura is never in tune. I thought something was very wrong with Indian music before La Monte introduced me to the Carnatic master singer Jon B. Higgins (at a Carnatic music festival at Wesleyan University, October 1969) and to Guruji [the term by which students refer to Pran Nath] the following year. Before meeting La Monte I didn’t understand what Indian classical musicians were trying to achieve. Later [La Monte] introduced me to the more rare recordings of classical Hindustani and Carnatic music, in which the performers pay much more attention to matters of tuning. When the tambura is in tune, it transports you to heaven—that’s the place to be! My own work changed entirely from that time on: I began to compose all of my music to a sine wave drone.

MB: What gives the drone its power?

CCH: [The drone is] a reflection of original sound. If you take a composite sine wave drone and you amplify it to 90–100 decibels, you hear a whole universe of sound; the drone contains every possible sound you would like to relate to.

MB: Did Pran Nath give you teachings about the drone and tambura?

CCH: Yes, and he emphasized that, besides the voice, it’s the only sacred instrument in Indian music, and it is central to the devotional practice of Nada Yoga. It is part of a prayer to play the tambura—and the raga that you sing is an amplification and elaboration of this prayer.

MB: Amplification?

CCH: The raga is contained as a substructure within the tambura sound.

MB: The raga is a certain shape within the tambura sound.

CCH: Yeah, the two are strongly correlated.

MB: Did you feel it was important to separate your study with Guruji from your work?

CCH: As I was trying to say, my initial encounter with Guruji’s music was so powerful that my entire concept of music went through a complete revision. My competence was in one blow reduced to that of a beginner. There was no place for a grand personal musical statement. But to be able to progress from this point on presupposed a singular devotion to a singular method of teaching. I dropped the whole concept of Western music after having studied with him for less than a day. Devotional music has no place for eccentricities such as “my music.” In a certain sense you have passed “beyond music.”

MB: What music has evolved out of Pran Nath’s coming to America?

CCH: Well, many people felt strongly influenced, speaking just for myself. I’m working on releasing a CD which I dedicate entirely to Guruji. This is my first CD. I never cared to release my music before, but someone got me started. It’ll come out as soon as there’s finance for the manufacturing. I have my own label, Etymon Recordings . . . the CD’s called The Electric Harpsichord.

MB: How much improvisation is there around the drone? Or is it more about sustained tones?

CCH: No, it’s actually the scale of Multani played on a well tuned electronic harpsichord. Although I am not trying to emulate the raga form but something different.

MB: Ah! That sounds fascinating. How long is the piece?

CCH: The piece is infinitely long, but this record is twenty-five minutes . . .

MB: Do you perform often?

CCH: No, never any more, because nobody wants to hire me. My last performance was over twenty-five years ago, and this record is a recording of one of my last performances.

MB: But you still continue to compose and play?

CCH: Yes, of course.

MB: Was there a diminishing of interest in work evolving out of Pran Nath’s teaching?

CCH: Well, again, nobody could claim that we were performing Guruji’s teachings when we were doing our own thing. Of course, La Monte and Terry [Riley] were professional musicians, but I was not. And, of course, our musicianship grew with our studies and that became increasingly noticeable. And, not being a professional musician, I didn’t understand the mechanisms of commercially viable enterprises, so between 1970 and 1976 I was only able to land a few gigs. The audience was very enthusiastic, but you could never find people to produce concerts. You had to do the whole thing yourself, like La Monte or Terry did—but in my situation, that meant too much extracurricular work. It cuts into your practice time, your meditation time, and I’m not prepared to diminish that part of my life.

MB: Is there a way that I can hear that recording?

CCH: The thing is, you need really good equipment to hear this. That’s one reason I was never enthusiastic about releasing records, because a home stereo is not an acceptable transmission channel. My music is very loud, like La Monte’s, and to hear the combination tones that I’m using you need to crank up the volume and play it at 90–100 decibels. And you could never do that at home. You could never really hear the piece, it’s sort of just a joke to play it on your home stereo. But people have been prodding me for so long, so I sort of gave in. Mainly what’s taken time is the booklet with my text, La Monte’s, and Henry Flynt’s. It’s a costly production, the booklet. I didn’t want to simply release a CD—it has to be put in context.

MB: It sounds like until the late 1970s there was some support for what you were doing.

CCH: It was simply that my mother was footing the bills for all my concerts! [Laughs] I came to the conclusion that that wasn’t a viable way of doing it. In other words, if I couldn’t get the institutions to pay for it, I should use the money differently.

MB: Was there a community of people doing work around Pran Nath in the early 1970s? What kind of activities were generated out of that enthusiasm?

CCH: We who pioneered this thing—we had no following, that’s my sense. My sense is that there was no following along this path because it was extremely demanding. For me, it was almost impossible to get commercial support for this type of concert. They were expensive to put on—20 thousand dollars to rent all the equipment needed to put the concert on, and I’m not talking about money for renting the hall. It was a very expensive production, and the money was simply not there. People in the position to arrange such concerts thought we were crazy, by our demands, that’s my impression.

I recall how Henry [Flynt] and I in the early ’80s were trying to put together an all-star band with Terry Jennings, but no one was prepared to support us. In the end if I wanted to play with other people I had to limit myself to Coltrane standards or other compositions that everyone already knows, and which required no amplification. I had a hard time convincing Henry to form our band Dharma Warriors, to which I brought Marc Johnson on bass—but by that time Terry Jennings had split to California and didn’t return East again. After a few rehearsals and one public concert Henry decided he had had it and packed up his instruments for good. He felt that the response to his efforts was entirely inadequate. That was a sad moment. I went on playing with Marc, who I introduced to Arthur Rhames, with whom I had just started to play. We had a live-broadcast concert at Columbia University—but as with Dharma Warriors, we were never asked to perform again. Of course, Arthur is a legend today.

MB: Who was the core group of musicians around Pran Nath in the early ’70s?

CCH: At first me, La Monte, Marian, and Terry [ Jennings]. Then a few others joined, like John Hassell. There were gigs in Europe for a while, and a couple of gigs in America, but basically nobody was there to produce the music. I remember going to all the record companies on sixth avenue, RCA, CBS, and so on, and they basically thought long duration compositions were crazy. And they thought La Monte was crazy. The only one they didn’t think was crazy was Terry [Riley]. He had a good deal with CBS, so long as David Behrman was producer—but [Behrman] stopped being the producer and Terry was cut off too. Few people understood that what we were doing was a good thing. We had no little or no access to the public domain after that. I mean La Monte’s concerts were basically private in the ’70s and ’80s and Terry [Riley] retreated to study full time with Guruji.

MB: Do you think Pran Nath suffered from a similar incomprehension?

CCH: Oh, absolutely. Not even we students could comprehend the depth of his teaching. He came from a tradition that we had not been schooled in. He opened our ears to dimensions that we had no idea about before he came.

MB: What would you say those dimensions are?

CCH: That music is a prayer, and music is your soul, and that it’s something that you devote your whole life to. You change your whole life to be in tune with his teaching. You can’t just do any- thing and also be a student of his music. You have to adjust so many things in order to be a meaningful student. All these adjustments meant that basically you went outside of society. So that’s basically what we did. And society thought we’d said bye-bye to the whole thing. They didn’t understand what we were trying to achieve.

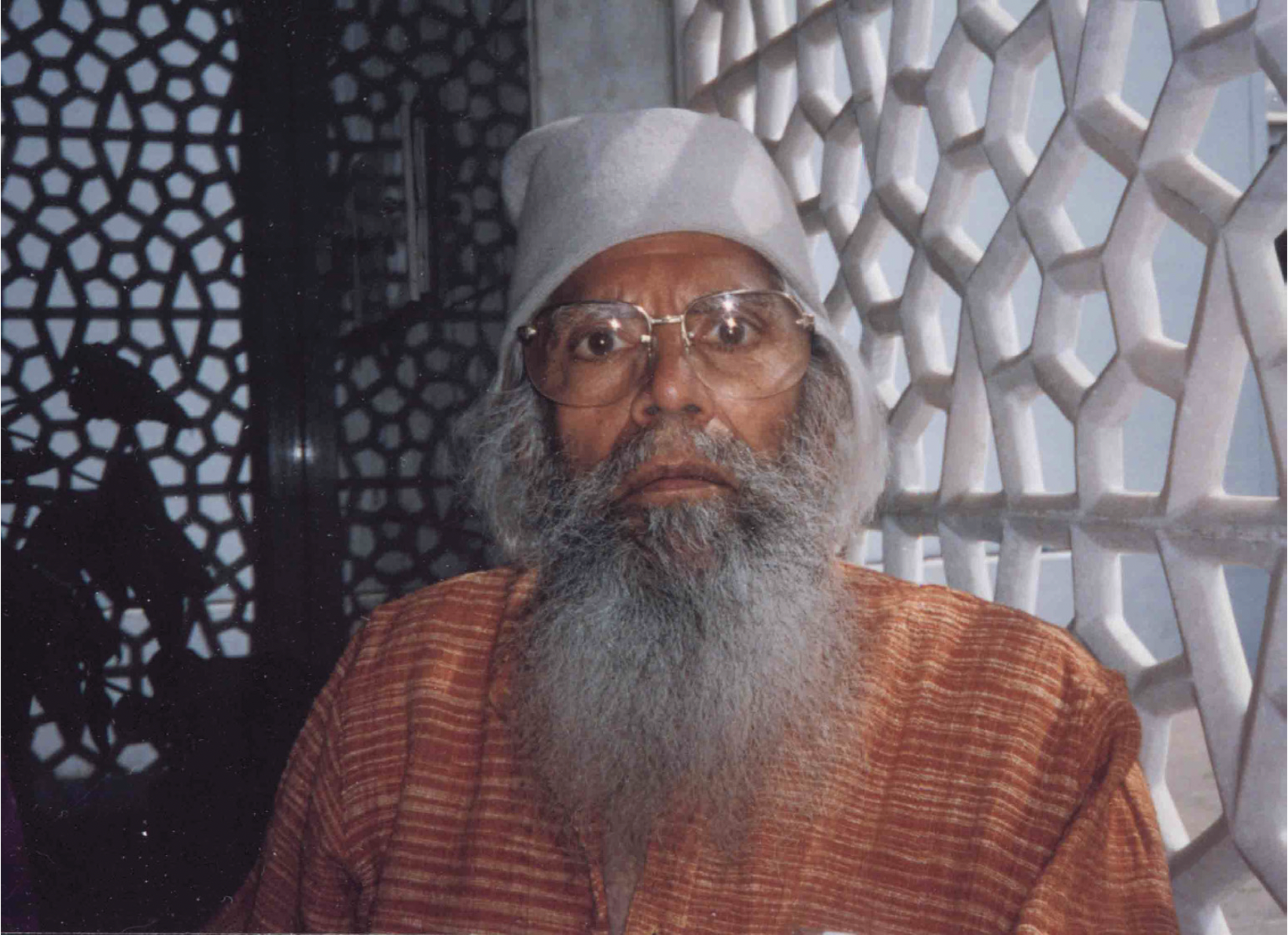

Pandit Pran Nath outside Nizamuddin Aulia’s darga, Delhi, 1994. Photo courtesy Rose Okada.

II.

MB: What is the most important advice that Pran Nath gave to you?

CCH: Noting that I did not feel comfortable to perform raga in public, he actually ordered me to do my mathematics first and then do the music without being pressured to perform. That sort of hampered my studies with him a little bit! He had such an admiration for mathematics, and he thought that somehow mathematics was preparing me for higher musical studies.

MB: What is the connection between raga and mathematics?

CCH: You get your first intuitive acquaintance with infinity through the raga, and then mathematics amplifies this concept of infinity by teaching you to formally manipulate it on paper with symbols.

MB: The infinity that the raga exposes you to. What qualities of the raga produce that experience of infinity?

CCH: The whole tuning system presupposes an infinity of notes. If you take the tambura sound and amplify it to 100 decibels, the number of pitches you hear is an infinite fold compared to what you hear without amplification. Not just the overtones, but the combination tones. See, when you have two sounds sounding simultaneously, there is a certain ratio between them. However, in Western music these ratios are never applied as sustained notes because the tempered scale only gives a rational ratio for the interval of the octave, while the remainder of the intervals are non-rational ratios. In just intonation the concurrent sounding of two tones yields a rational ratio also for all other intervals that are applied—not just the octave—and this property is also inherited by the combination tones of all orders generated by any two notes forming a rational interval. You cannot hear this in western music because every interval except for the octave is out of tune. If you think about amplifying the raga, you get this infinity of notes. The louder you play the sound, the more tones you hear simultaneously. Taken to a limit, you will hear an infinity of tones.

MB: How does the raga itself relate to the infinity of tones produced by the tambura?

CCH: Well, that’s a particular path through this infinity. Because it’s such a large collection of tones, many paths go through it, and each raga defines its own paths through this infinity. You can’t comprehend the entirety of infinity, so the raga gives you a particular set of paths—you grasp the infinity from different angles through doing different ragas.

MB: Is a raga a finite shape against a backdrop of infinity, or is it more complex than that?

CCH: I think so [that it’s more complex]. You can listen many times to the same recording, or different performances by Guruji of the same raga and you hear different things every time. Another musician you hear that with is Sri Rama Ohnedaruth [John Coltrane]: Every time you listen to him, even if you’ve heard it a thousand times, you still hear a new thing every time. This shows that the raga is more than finite. Not infinite, but the point is that the soul is a limitless entity—it has no limit. If you take the picture of the raga as a living soul, then the soul has no limits—it’s limitless.

MB: So how do we talk about [raga’s] taking on form?

CCH: Well, it’s a path through this infinity—it takes you through different stages of this infinity.

MB: And what makes it more than finite? Is it a question of time?

CCH: No, it’s a question of attention. You always hear a new thing when you listen to a recording of a rag by Guruji because his sing- ing always inspires and invites you to a possible refinement of your tactics of attention. The continuous refinements of your tactics of attention bring you to points which you hitherto have not visited, and the paths described by these never ending points of attention are points of existence tending towards a potential infinity materialized by repeated listenings. You come to a very practical understanding of the credo of nominalism: existence is attention. That is, infinite existence presupposes infinite attention. This concept is not only a matter of aesthetics, but, more prominently, a matter of ethics.

MB: And how does one enter into this infinity?

CCH: As long as you can keep adding one, without coming to a point where you have been previously, then you are in infinity.

MB: And that’s part of the design of the raga—that it has this opening out onto infinity?

CCH: That’s my feeling about it. I will not say that’s what Guruji said, but this is what I understood him to say. He never used these particular words, of course. But again, we were born in the western world; we were not brought up with this. If I were born in India I may have a much better understanding of this whole process.

MB: Are you comfortable with the way the process has played out as a Westerner?

CCH: As long as one is trying one’s best, that’s all you can do. As long as you don’t stay in the same place.

MB: How did Pran Nath feel about the kind of music that was evolving out of his coming to America?

CCH: He probably felt rather lost about it, in the sense that he didn’t have anything to say about it, that was his way of talking about it. I think he was quite distressed that we tried to do what we did. He never liked my music when I played it to him—he really didn’t like La Monte’s music either. La Monte dedicated The Well Tuned Piano to him, and gave him the first copy, but he put it under the bed and never listened to it. The only thing he liked about my work were my paintings. I’m afraid he had a low opinion of my music, and La Monte’s.

MB: And Terry [Riley]’s music too?

CCH: Yeah. I don’t think he understood what we were trying to do. I remember La Monte playing him John Coltrane, and [Pran Nath] was very taken with him. Coltrane’s music has a common relation with Indian music (or Swedish folklore), via the blues scales, but is otherwise divorced from Guruji’s roots; yet he could feel the enormous soul behind Coltrane’s music. I don’t think [Pran Nath] felt we were up to Coltrane’s level. [Laughs] Guruji was sometimes, I think, even annoyed by what we were doing. He probably thought we should have practiced tuning the tambura and singing our scales instead of doing our own adventures.

MB: You’re inferring this from his silences . . .

CCH: Yes. He was extremely concerned about our wellbeing. As I said, he was such a wonderful person, he would never interfere with what you were doing as extracurricular work. He would never tell us to stop doing these things, as opposed to the way he corrected us during the lessons he gave. But he was not enthused about them either, again, as opposed to the affirmative mode under which he conducted his teachings.

MB: Did he ever get involved with electronics?

CCH: Well, he invented a design, Prananada, for amplified tuning forks. And he did appreciate the sine wave generator as a reference tool for tuning the tamburas. He was intrigued by the sine waves. Purity of tone was basically his message. He just didn’t feel that western instruments could compete with the human voice or the tambura. And I agree with him completely. But we just couldn’t match his degree of mastery in this area—it would have been ridiculous for us to try to sing ragas or something in public. Although La Monte and Terry have done that very well—but compared to what [Pran Nath] was doing, it was just student work.

MB: But he founded these schools in America . . .

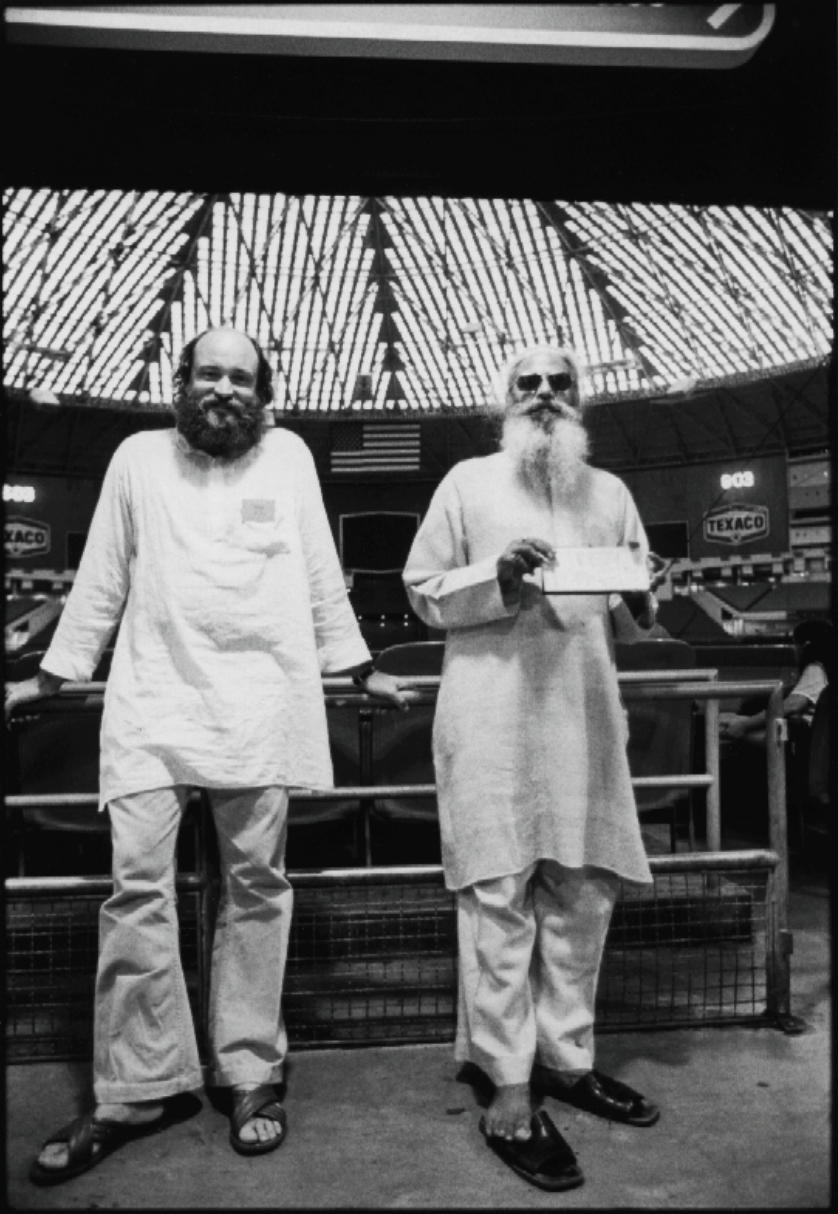

Terry Riley and Pandit Pran Nath, Houston Astrodome, 1973. Photo courtesy Terry Riley.

CCH: Not exactly. La Monte and Terry [Riley] simply founded these schools on their own. I don’t know if [Pran Nath] actually . . . although it is true that he had taken a vow to ensure the continuation of the tradition of his school of music.

MB: But these schools had his blessings . . .

CCH: No I am not sure we had his true blessings at all. If we had gone to India and renounced all material comforts and sang in a cave, that would have been a tribute to him. But he didn’t think that The Well Tuned Piano, or my piece, was a tribute to him. He just couldn’t understand why we were wasting our time on those things. But this was our way of trying to understand the implications of his music. We had to do it on terms that we were familiar with some- how. We were trying to approximate his message—but it was only an approximation. It was not the real thing. And if it wasn’t the real thing, he wasn’t interested.

MB: What did he think about amplification?

CCH: I think he thought it was unnecessary gadgets. He told us to simply put the ear to the neck of the tambura if we wanted to hear what was going on, to learn all the subtleties. He was used to singing in caves and temples where you have natural amplification. Nevertheless, he invented and never disowned the Prananada, so he didn’t have a prejudice.

MB: And recording?

CCH: Guruji was not friends with making records. He thought that was a very disturbing aspect of western culture. We were not even supposed to take notes. He got very annoyed when we tried to write down what he was saying. He comes from a tradition where you listen to your teacher and remember every word, every subtlety of the encounter. Your ability to absorb those moments defines you as a musician. And if you needed notebooks and tape recorders and such, that only meant that you are a very weak musician. The point is that attention to records of any kind distorts your sense of present tense, which is the grammatical timeframe that you need to occupy as a fluent practitioner of the language of music.

MB: I assume there were lots of tape recorders around him when he taught?

CCH: Yeah. But I think he could not imagine that that could con- tribute to our understanding. He learned what he learned by being devoted to his teacher. He could not imagine that there was any other way.

MB: What was your impression of how he dealt with American life?

CCH: I think you have to consider his relation to India. He could not find any disciples in India. Indian music at that time was at its lowest. They preferred Elvis Presley to Ravi Shankar even. So this was his last chance to preserve what his teacher had given him.

MB: Were there contemporaries or students that he saw as carrying on his lineage?

CCH: No. He could never find a good student in India. He almost never spoke about contemporaries. When we brought him a record [by one of his contemporaries] he said, “very good musician,” but then he didn’t say more. He never spoke badly of any of his colleagues. Although, he gave us anecdotes—say, that when the Ali brothers [Salamat and Nazkat Ali Khan, whom Pran Nath had apparently given lessons] were singing, all the masters left after ten seconds. Indian music has extremely high standards. It was no joke; it was not entertainment. It was devotional music. We don’t know that concept in the west, except for Gregorian chants.

MB: Do you think that will return? Is that part of the meaning of Pran Nath’s legacy in America?

CCH: I know there’s a renaissance in Indian music in India. But Western music has just gone down the drain. It went from bad to worse. I haven’t heard a new composer since La Monte Young. Nothing is being produced that is worthwhile.

MB: The energy is in popular music . . .

CCH: It’s not that. The whole western lifestyle is geared to things that are irrelevant, or even an obstacle to this type of music. You can’t live in Manhattan and study ragas unless you’re very exceptional like La Monte and Marian and maybe Michael Harrison.

MB: To what degree did Pran Nath turn you on to a spiritual path, or music as a spiritual path?

CCH: I didn’t understand there was this connection until I met him.

MB: Has your spiritual practice continued to evolve through Pran Nath?

CCH: Yes, everything I have in terms of spiritual practice I owe to him.

MB: What was his advice concerning spiritual practice?

CCH: That work was the fundamental feature of life. That you should make your life your work. To work as much as possible. Work that is a tribute to God—that exposes the greatness of God. That’s why he felt that mathematics was so important: because it was the only western activity that exposed the greatness of God. He didn’t think highly of any other western activity.

MB: Was he surprised at the absence of the sacred in the west? How did he feel about New York City in the ’70s?

CCH: Oh, he was extremely unhappy about it. The only time I remember he was enthusiastic, we were in San Francisco. He liked to watch TV, and we were watching a program about the whales. Then he heard the whales sing and he started to cry. That was his most profound spiritual experience of the western world.

III.

MB: Can you talk a little more about who your formative musical influences have been?

CCH: Besides Guruji and Coltrane, the other person who changed my mind about music was La Monte Young. I think he has a very profound approach to music, and I like his music from the ’60s very much, especially the duos that he and Marian were singing just with the sine wave drone [i.e., Map of 49’s Dream].

MB: Was La Monte doing a lot of experimenting with that style?

CCH: Well, he and Marian sang almost every day.

MB: Were they singing ragas?

CCH: No. I mean, they could sing ragas in between. When we were walking in Manhattan, they could just start singing a raga on the street, which was very nice, but he never tried to imitate raga in his own work. No, Marian was singing sustained notes and he was improvising over the drone and her sustained notes. He had a system called the Two Systems of Eleven Categories; in my opinion it’s the most important theoretical work since the Notre Dame School in the Middle Ages in western music. Because it’s a direct continuation of that type of thinking. See, when they started with equal temperament in the Renaissance, they basically destroyed the spiritual space of music.

MB: [Laughs] I find it such a wonderful thing that there’s so much room left to explore!

CCH: Yes, that’s the point. As a composer, I had recognized the crisis of the contemporary music scene when I met La Monte in 1969 because basically Stockhausen and Xenakis had taken western music to its limits. There was not much more you could do! Which is proved by what happened afterwards, because nothing happened afterwards. Neither Stockhausen nor Xenakis could improve on what they’d done in the ’60s—they just basically repeated it or watered it down. There was a crisis in western music because there was basically nothing interesting you could do. Then this concept of Just Intonation was brought back by La Monte. That was simply alien to western music, and he was the only one at that point that considered that idea . . .

MB: Well, there was Partch . . .

CCH: Yeah, but with him it was cluttered with so many other ideas. La Monte went to the bare bones of it and stayed with the fundamentals of it. He’s a loner in this context. He really showed discipline, not trying to do a thousand things, but just one single thing: being in tune. That type of discipline is what you need from every composer. I think his position is very admirable.

MB: What are the implications of Just Intonation for the music of the future? It opens up a vast territory that simply hasn’t been looked up, but beyond saying that, I don’t know what to . . . expect . . .

CCH: Are you familiar with the Notre Dame School and Leoninus? If you go back and study that music, you will find that it was spectacular. You must understand that these were the people that introduced the first drones in the Notre Dame Cathedral—the big organ . . . That was the biggest sound ever heard in Europe. They just played the pedal point, they didn’t play melodies on the organ— it was pedal point!

MB: So it was just one massive blasting drone . . .

CCH: Yeah! And in that big cathedral, right? And then they had people singing over it. That was the biggest revolution in western music, that idea of a big sound. But it was cut short because of the introduction of the keyboard, which resulted in the need for re-tuning all the scales, and that just destroyed what they’d started to do . . . and you only have it left in Gregorian chant today.

MB: Were there heretic drone schools in the Middle Ages?

CCH: No, they weren’t heretics at all—they were the masters. But the keyboard just couldn’t accommodate it . . . If they had had the money they would have produced a keyboard for each scale. But they were short on money, so they just had one, and they forced everybody else onto that keyboard.

MB: And the music of the future will have that infinite number of keyboards . . .

CCH: I would think so. I mean the computer can certainly help here. It makes it much cheaper to have all these keyboards around . . .

MB: And mathematics?

CCH: Yeah, and a little dose of mathematics will help too . . .

MB: To what degree is there a systematic exploration of the different ways of tuning in Just Intonation? Is there a consensus as to what kind of tunings are the most potent or satisfying?

CCH: No, I don’t think so. Because first of all there’s no a priori tuning which is the optimal. You simply choose the tuning that is aligned with your way of thinking. You have an infinite number of possibilities here and each composer should simply have her own concept of tuning. That seems to me basically the future of music. Instead of everyone using the same system of tuning, each composer works out her own system of tuning and makes music accordingly.

MB: What governs your choice of tuning?

CCH: I think that’s pretty subjective. Again, you have an infinite number of possibilities. You have to have a discriminating mind to choose one which is attractive to more people than just yourself.

MB: Will there be a holy grail-like search for some remarkable tuning method that exists somewhere in the infinity of possible tunings . . .

CCH: Yes, of course, that will always be the lure, the myth, so to speak of the composer’s destiny. Whether the composer will find it or not is an empirical question.

MB: What is the ratio of the known to the unknown in this?

CCH: Oh, it is basically one to infinity! [Laughs]