Jerry Hunt with his wands outside North Texas State University, Denton, 1976.

I have formed a group for publication recording and so forth and had wanted to write you before now about this. I would like to have your music as part of this activity: it is not a happily [sic] business activity but serves I think now only the purpose of sending the things out. If you would have any interest in this, let me know also: I can go into details then: I will try to get a promo copy of the first to you soon. It started innocently enough with me wanting to make a record (everybody has done it, I felt left out)—and has grown in intention as I am on the second one now Texas Music and am trying to get a sense of the next five before a publicity phase in September/October begins for distribution and so forth.

This is not a money maker, but there is the real possibility of having it pay for itself by limited edition sales of things, and that is the path I am pursuing now: a: limited edition is produced with special graphic and sold at inflated prices—$25 each and that holds the cost for that one and makes some money available for covering the total loss of distribution—a situation where you send them out and there is nothing coming back 18 months later a check for $3! Not a promising situation.

Best and thanks for your effort on this piece. Hopefully some for this area and that the information helps. Will send notes as above with this.

Jerry Hunt, letter to James and Marky Fulkerson, May 1979.

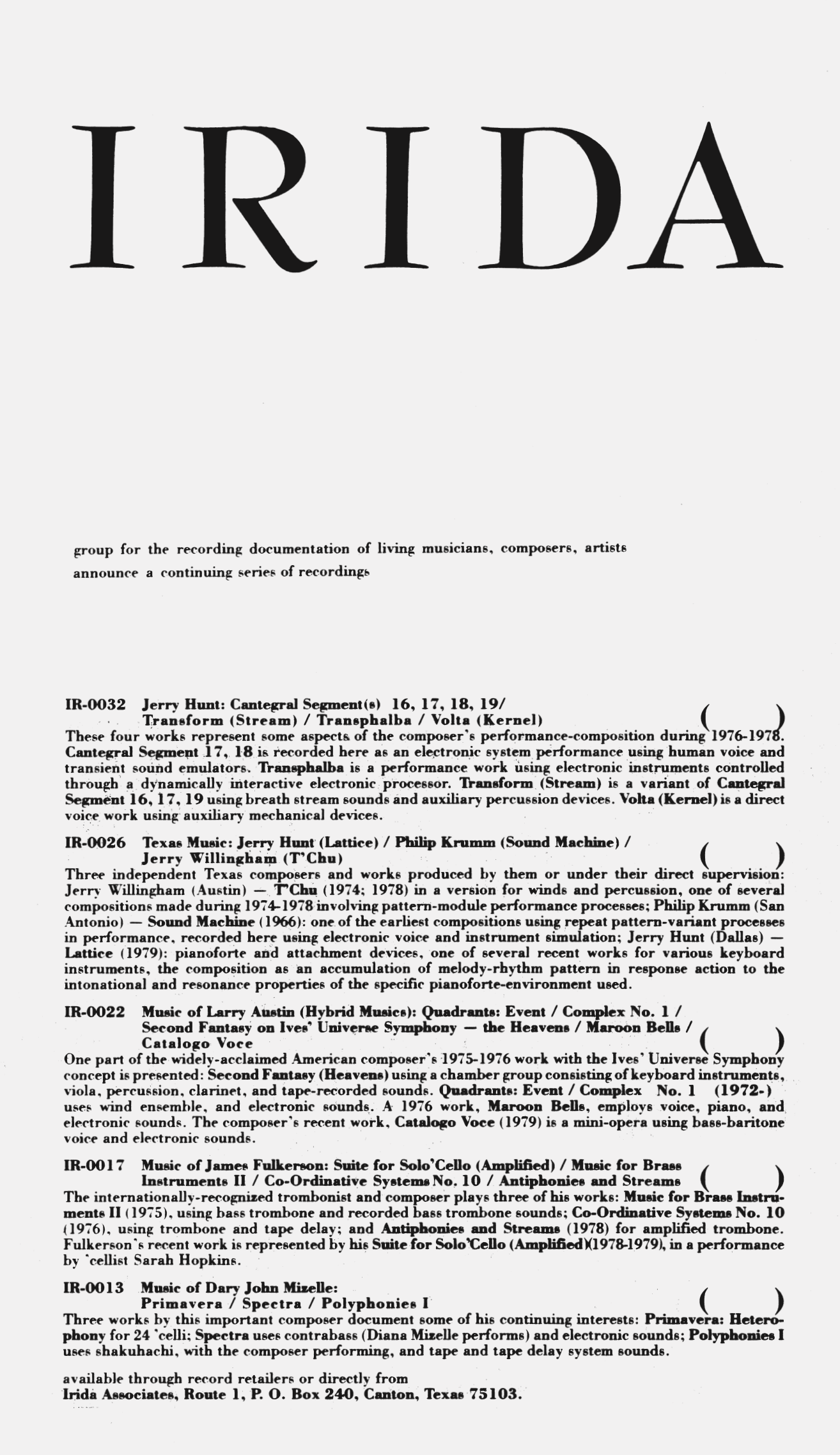

Irida Associates U.S.A., an obscure record label founded by the musician-composer Jerry Hunt, was contactable for its decade-long existence at Post Office Box 240, Canton—just a quick drive from Phalba, equidistant from Cana—a remote area in rural North Texas. The label produced seven non-sequentially numbered LPs in unknown editions between 1980 and 1986. 1 Irida focused on new and adventurous contemporary music with a strong propensity towards Texan and Texan-adjacent artists, including Jerry Willingham, Philip Krumm, James Fulkerson, Gene De Lisa, Robert Michael Keefe, Rodney Waschka II, Dary John Mizelle, Larry Austin, BL Lacerta, and Hunt himself. Relatively unknown in their time, the label’s releases now stand as essential documents of the nascent activities of composers working along the Third Coast.

Hunt hooked the term Irida—the Sinhala word for Sunday, associated with the name of a pre-Buddhist sun god 2 —from a Sri Lankan art gallery in Berlin owned by his high-school friend Fred Reisman, who may have offered to stock copies of, or otherwise support, the label’s releases. Hunt once called Irida “a vanity project,” an outlet for his music and that of his friends and other fellow travelers. 3 He often commented on the label’s inability to turn a profit and seemed bemused to be in the record business at all. To get the label off the ground Hunt raised funds from the contributing composers and a few patrons, and made up the difference himself. He and his partner Stephen Housewright worked with A&R Records, an affordable pressing plant based in Dallas, to produce the records. They assembled the materials themselves, fulfilling orders from interested parties across the country, and even employed the aid of Hunt’s mother, Johnnie Imogene “Jean” Hunt, to whose house they had stacks of LPs and jackets delivered. While Hunt had started the label on Swiss Avenue in Dallas in 1979, in the winter of 1981 the couple moved into a barn on Hunt’s parents’ property outside of Canton, sixty miles east, eventually turning the structure into their permanent home, which doubled as the Irida headquarters (giving the Canton post office box as the label’s address). To help subsidize the process Hunt engaged painter Salle Werner-Vaughn and assemblage artist David McManaway, his friend and frequent collaborator, to make limited edition fine-art prints that could be sold with the records at higher prices. Hunt gave the endeavor five years, claiming he could take advantage of a tax loophole if it didn’t turn out to be financially viable. 4

Jerry Hunt at Salle Werner's studio, Dallas, ca. late 1960s or early 1970s. Courtesy Stephen Housewright.

Although Hunt wasn’t the sole record producer in Dallas’s avant-garde music scene in the ’60s and ’70s, he was nevertheless at the center of it. By all accounts a virtuoso pianist, he cut his teeth playing the upright in Dallas strip clubs as a teenager—in the vicinity of Jack Ruby’s Carousel Club—and simultaneously nurtured an interest in experimental and electronic music. Starting in the early ’60s, Hunt gave classical recitals of Rachmaninoff, Chopin, and Debussy, but quickly expanded his repertoire to include more adventurous contemporary New Music. In the mid-’60s he met clarinetist Houston Higgins and began an active collaboration, founding and codirecting the Dallas Chamber Ensemble in ’66 along with David Ahlstrom. The group performed pieces by Charles Ives, Erik Satie, Anton Webern, Igor Stravinsky, and Béla Bartók, new works by Karlheinz Stockhausen and John Cage (whom Hunt hosted on his visits to Dallas), premieres for emerging composers such as Gordon Mumma, and held at least one tape music concert featuring work by the obscure Dutch electronic composer Ton Bruynèl.

Hunt’s engagement with electronic music extended to making early homemade components and synthesizers, and to founding the Video Research Center with David Dowe in 1970, which operated out of the basement of an abandoned football stadium owned by Southern Methodist University in Dallas. There, he and Dowe branched out to produce nonrepresentational video work for public-access television, and Hunt began using these audio/video systems in performances of his own work. As his interests became increasingly reliant on video and musical technology, the Dallas Chamber Ensemble morphed into the Audio Visual Studio/Ensemble, with an expanded rotating cast of musicians and technicians that included Higgins, Philip Hughes, Ron Snider, and Gordon Hoffman. The group still performed contemporary works by Stockhausen and Cage as well as compositions by Hunt and the other members. 5, 6 By the end of the ’70s, Hunt claimed to have given up playing the piano to pursue what he referred to as “interrelated electronic, mechanic, and social sound-sight interactive transactional systems”—but he would continue to give private piano recitals in Texas nonetheless. “Lattice,” which appears on the 1979 compilation Texas Music, one of the first Irida releases, features Hunt performing on the instrument.

Jerry Hunt and Ronald Snider, ca. late 1970s. Photographer unknown. Courtesy Stephen Housewright.

The many threads of Irida are fairly easy to connect. The first two records from 1979 feature Hunt’s own work: the solo record Cantegral Segment(s) 16.17.18.19. / Transform (Stream) / Transphalba / Volta (Kernel) and the compilation Texas Music, which, opposite Hunt’s “Lattice” on the A side, included Phillip Krumm’s “Sound Machine” and Jerry Willingham’s “Ta Ch’u” (named after the I Ching hexagram; the original sleeve read “T’Chu” as the result of a typographical error) on the B side. Willingham was a somewhat elusive figure who was engaged in experimental intermedia collaborations with dancers and poets in Dallas and Austin when he first encountered Hunt in the early ’70s. The two maintained a friendship through most of the decade and kept up a correspondence when Willingham moved to Stuttgart, Germany, in 1980. Similarly, Krumm, originally from San Antonio, has a rich story, though he remains an underknown figure in avant-garde music. He first met Hunt in the spring of 1963 at a ’pataphysics conference organized by the writer Roger Shattuck. Hunt and Krumm became fast friends and later that year were on the road to Massachusetts at the invitation of Phil Hughes, a friend of Hunt’s from Dallas, to perform with the Brandeis University Chamber Ensemble on November 15, 1963. (Along the way they stopped off in New York and stayed with Krumm’s friends Dick Higgins and Alison Knowles.) In 1961, Krumm had been a student in Ann Arbor, where he was associated with the ONCE Festival and its organizers, including Robert Ashley and Gordon Mumma. One can assume he was the person to have introduced Hunt to Ashley’s work, which Hunt performed at Brandeis along with his own composition “Helix,” Krumm’s “May 62,” and pieces by Stockhausen, Toshi Ichiyanagi, and George Brecht. Alvin Lucier, who conducted the ensemble, recalls that their concert caused “quite a stir,” and was the first of its kind at the school. “Do I remember correctly,” he says, “that they [had] strewn the concert hall with toilet paper?” 7

In the mid-’60s, and with Krumm and Lucier as key contacts, Hunt began to participate in the burgeoning American New Music scene, particularly its Bay Area cluster. He visited the San Francisco Tape Music Center in 1966 to further experiment with electronic composition, and soon purchased a Buchla Electronic Music System of his own. The following year, Larry Austin founded the magazine Source: Music of the Avant Garde at University of California, Davis. Hunt submitted a number of scores including “Sur (Doctor) John Dee” and “Tabulatura Soyga” for publication, and they were edited by Austin’s then-student Dary John Mizelle and included in the second issue; Hunt later complained to James Fulkerson that Source had completely mixed up the materials, presenting parts of three different scores as “Sur (Doctor) John Dee,” making them indecipherable (though it’s worth noting that interpreters leveled accusations of indecipherability at all of Hunt’s scores, no matter how the pages were ordered).

8

Hunt’s inclusion in Source proved to be an important touchstone for the composer, who maintained relationships with its editors. In 1969, Mizelle commissioned Hunt to perform “Helix” at Sound Tunnel, an installation work by Eric Orr that had recently been built at the Los Angeles Junior Arts Center. When Austin left Davis for a teaching position at the University of South Florida in Tampa, he organized the Intermuse Festival, an academic conference comprising a series of performances and talks at the Chinsegut Hill Manor House (then affiliated with the university) in January 1976. Hunt, Mizelle, and Fulkerson all presented new works; Mizelle premiered “Polyphonies I,” a semi-improvisational work for shakuhachi and electronic tape, later included in his Irida release. Fulkerson writes that he was impressed by the combination of theoretical depth and humor in Hunt’s performance. Their encounter proved to be formative for both artists, and Fulkerson would go on to be one of the primary interpreters of Hunt’s compositions in the years to come. Austin’s time in Tampa was short-lived; he was soon forced from his Florida teaching position after only two years due to his adventurous curricula. Fortunately for Hunt, Austin relocated to Denton to teach at the University of North Texas (his alma mater), where the two composers reconnected.

Perhaps the most elusive Irida release is the curious Music of BL Lacerta from 1980. The BL Lacerta Improvisation Quartet was a four-piece “orchestra in miniature” founded in 1976 by a group of University of North Texas music students who performed frequent, spirited concerts of spontaneous music. The ensemble’s shifting membership included violinist Maurice Hood, clarinetist Robert Price, tubaist Les Gay, and percussionist David Anderson. While Lacerta and Hunt had sprung from the same groundswell of Dallas New Music activity—Price, as a teenager, had attended Hunt’s concerts at the home of his high school classmate Mark Srere (the son of Hunt’s patrons Paul and Oz Srere), and David Anderson had studied under Merrill Ellis, Larry Austin’s predecessor at the university—the group cannot place the exact origins of their collaboration with Hunt. (They do recall visiting him for dinners at his Swiss Avenue home in Dallas, where he had a habit of setting out small dishes of food for his rats, to ward the pests away from his pantry.) BL Lacerta would remain a fixture in the Texas arts scene for a number of years after (a version of the group, led by Anderson, persists today), playing alongside a wide array of guest musicians and performers, including John Cage, Pauline Oliveros, and David Behrman—not to mention Jerry Hunt himself, in 1985, as part of a concert series at the Bath House Cultural Center in Dallas.

Irida Records stock list, ca. 1981.

While Irida was a short-lived venture, it marked an important moment in Hunt’s trajectory. By his own account, Hunt had entered a new creative phase in 1978, developing his beguiling solo performances in which he would gesticulate across a concert space, interact with totem-like objects, and trigger an array of electronic audiovisual responses that seemed both random and imperceptibly coherent. The label arrived concurrently with the maturation of Hunt’s voice as a composer-performer, and anticipated a decade of increasingly active touring. He performed his works more frequently at festivals including New Music America and the Composers Forum, academic conferences such as the American Society of University Composers, and alternative arts spaces including Experimental Intermedia and Roulette in New York, as well the European institutions Het Apollohuis in the Netherlands and the Logos Foundation in Belgium. At the same time, Hunt found opportunities with grant-giving organizations, most notably the National Endowment of the Arts, who were in the process of broadening the scope of their regional funding.

By the time Cartography came together in 1986, Hunt, for all intents and purposes, had stopped putting out Irida records and was slowly distributing its back stock. Through his connection with Larry Austin, Hunt had been working in the University of North Texas’s Center for Experimental Music and Intermedia to develop “Fluud” (1985), his sole piece for the Synclavier II. Rodney Waschka II, a student of Austin’s who had heard his Hybrid Musics (1980), approached Hunt about releasing a record of compositions for the instrument by him and his fellow students Gene De Lisa and Robert Michael Keefe. Cartography would be the final release on the label, as Hunt’s energies shifted toward his solo performances and collaborations with figures such as dancer Sally Bowden, performance artist Karen Finley, and intermedia artist Maria Blondeel, activity that only seemed to ramp up in the final years of his life. In 1992, one year prior to his death, Hunt worked with Joseph Celli’s O. O. Discs label to release the CD Ground: Five Mechanic Convention Streams (1992), comprising five pieces from his “Ground” series, and the posthumously published VHS Four Video Translations (1995), a collection of Hunt’s performative video works. 9 The tape, recorded toward the end of Hunt’s life, when he was suffering from late-stage cancer, was intended to distribute his highly personal performance style without the artist needing to be present, thus serving as a striking message from beyond. In this light, the collected works of Irida can also be considered as a sort of communiqué from a time since passed—a freewheeling moment where the possibilities for composition and electronics seemed boundless—conjuring images of the late artist, his partner, and his mother assembling records in rural Texas, and of a group of mavericks making work on the fringes of the Third Coast.